Birds of Copan

H. Bradford

5/22/19

This past winter, I was able to travel to Central America. One of the highlights of the trip was a visit to the Copan ruins in Honduras. Before I continue, it is important to note that Honduras has been experiencing political violence and repression since the 2009 coup that overthrew democratically elected president Manuel Zelaya. The United States has supported the coup in a number of ways, such as normalizing relationships with and recognizing the subsequent government. The United States has continued to provide military aid to the Honduran government, despite state violence of activists fighting for environmental, indigenous, and human rights. The following is about birds, which seems pretty trivial and privileged. For more information about the political situation, I found that “The Long Honduran Night Resistance, Terror, and the United States in the Aftermath of the Coup,” by Dana Frank was useful in providing an overview of the U.S. role in destabilizing the country. I feel that I can’t talk about the fun topic of birds without at least acknowledging the more serious social context, which I was sheltered from as a leisure seeking tourist. The only indication that anything was amiss was a power outage that locals at Copan blamed on the government as a way to thwart New Year’s eve celebrations and the large number of armed police/military/guards.

While I could have traveled to Honduras for more noble reasons, such as with a Witness for Peace delegation, I was there as a tourist. As a tourist, I visited the Copan Ruins. The Copan Ruins are located near the border with Guatemala and it represents the southernmost city of the Mayan civilization. Mayan “civilization” itself sounds rather racist, as Mayans are still alive, have (what wasn’t destroyed or repressed) cultural continuity with pre-Columbian Mayans, and certainly accomplishing important things. I suppose when this word is used is it to describe Mayans before the arrival of Spanish and before the abandonment of cities and monument construction at the end of the Classical period. Copan was a powerful Mayan city state located in the Copan River valley of Honduras. People in area had been constructing stone structures since 9th century BC, but the dynastic history of Copan begins in 426 AD and ended between 800 and 850 AD. At its peak, over 20,000 people lived in the city. It is a World Heritage Site and an impressive complex of what seems like an endless array of ruins and stelae. The site includes a ball court, Acropolis, stairways, residences, stelae, temples, tombs, altars, and other ruins. There is a lot of history to absorb and it is a lot to explore the entire complex. As fascinating as the ruins are, they are surrounded by forests which burgeon with birds! My attention was divided between history and ecology. In the end, my love of birds probably won and that was what I absorbed most from the experience. Yet, these things aren’t entirely at odds, since many of the birds had a place in Mayan culture. Birds are history as much as the monuments! Here is an overview of some of the birds that I saw and how they might relate to Mayan or regional culture.

1. Scarlet Macaw (Ara Macao):

A Macaw at Copan, H. Bradford 2019

A large number of Scarlet Macaws can be found at the Copan ruins. I spotted over twenty while meandering around the ruins. They seemed most plentiful on the main trail from the visitor’s center. The red parrots are hard to miss, as they are large, loud, and bright. The large number of Scarlet Macaws has to do with the nearby Macaw Mountain, which rehabilitates, breeds, and releases Macaws. Other birds are also kept at Macaw Mountain, often as permanent residents because of injuries or health conditions the birds sustained while kept as pets. There are feeding stations along the trail to the ruins (Whitely, 2015). They are the national bird of Honduras. Scarlet Macaws were culturally important to the Mayans, who, like the Aztecs, believed they symbolized the sun. Mesoamericans also traded the birds, which have been found in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. The bird remains found in Chaco Canyon date back from 900 AD from captive stock of parrots (Greshko, 2018). Macaws may have had ancient population decline due to this trade. Scarlet macaws are native to tropical lowlands where Mayan civilization was most concentrated and they require pristine conditions to survive, as they nest in tree trunks. Macaws are sensitive to deforestation, poaching, pet trade and are rare in the Yucatan peninsula. Today, they are more commonly found further south in Central America such as in Costa Rica (Stuart, 2015). Thus, the trade in parrots is why the macaws are found at Copan today, as the modern pet trade resulted in the need to rehabilitate the birds and eventually reintroduce them to the area.

Beyond trading them, they appear in Mayan stories. Popol Vul, the ancient Mayan creation story, features a deity called Seven Macaw, which is a bird creature with some characteristics of macaws, but also characteristics of a snake eating hawk (Hellmuth, 2015). In Popol Vuh, the Hero Twins, the central characters of the story, use a blow gun against Seven Macaw, which is perched atop a nance tree, which is a a type of tropical fruit (Iconography, characteristics of painted macaws on Early Classic, Tzakol, basal flange bowls, 2014). In the Popol Vul, Seven Macaw describes himself as such:

“I am great. I dwell above the heads of the people […] I am their sun. I

am also their light […] My eyes sparkle with glittering blue/green

jewels. My teeth as well are jade stones, as brilliant as the face of the

sky. This, my beak, shines brightly […] My throne is gold and silver.

When I go forth from my throne, I brighten the face of the earth.

Thus Seven Macaw puffed himself up in the days and months before

the faces of the sun, moon, and stars could truly be seen. He desired

only greatness and transcendence before the light of the sun and

moon were revealed in their clarity.”

(Helmke and Jesper, 2015: 28)

Copan ruins are the only place to see a specific depiction of a macaw (as the deity itself is not necessary a macaw) as this deity. There is a depiction of a scene wherein one of the twin’s arms in the beak of Seven Macaw (Iconography, characteristics of painted macaws on Early Classic, Tzakol, basal flange bowls, 2014). This depiction is located as an architectural decoration near the ballcourt. However, I did not know to look for this scene. Here is a replica of that artwork:  A replica of a ballcourt decoration at Copan representing Seven Macaw, (Museum of Mayan Sculpture, Copan, Honduras). Photo by Mark Cartwright, 2014

A replica of a ballcourt decoration at Copan representing Seven Macaw, (Museum of Mayan Sculpture, Copan, Honduras). Photo by Mark Cartwright, 2014

Seven Macaw is one of four Mayan “Great Bird” deities, which represent the moon, sun, stars, and darkness. Popul Vuh discusses the death and defeat of the bird, which was a prerequisite for pacifying the world to allow for the creation of humanity. To defeat the bird, the Twins tricked it after hitting it with the blowgun. They told the bird that they were bringing a healer, but instead removed its teeth and eyes, which served as the source of its power (Helmke and Jesper, 2015). Aside from the depiction of Seven Macaw, Copan ruins feature a macaw head ball court marker. Elsewhere, macaws, or at least stylized macaw like birds, are depicted on bowls, other ball game hachas. From the 2nd century onward, Mayans regularly featured Macaws in their art (Hellmuth, 2015). In the Late Classic Mayan period, macaws are the most commonly depicted land bird (Stuart, 2015).

Photo from the ball court, H. Bradford 2019

H. Bradford, 2019

2.) Montezuma Oropendola (Psarocolius montezuma):

Montezuma Oropendola, H. Bradford 2019

This large bird with an unwieldy name ranges from southern Mexico to Panama, occurring mostly along the Carribean side of Central America. It is an Icterid, or member of the Icteridae family, which consists of new world blackbirds, new world orioles, bobolinks, meadowlarks, cowbirds, and grackles. Although it is in the blackbird family, it really doesn’t look like a blackbird, as it is larger, with a large red and black bill, chestnut, black, and yellow plumage, and bare skin by its eye. Montezuma Oropendola is considered common, is omnivorous, and can be found in evergreen lowlands, forest edges, plantations, and disturbed forests (Sample and Kannan, 2016). I spotted at least two of them near the park entrance at Copan ruins. The name of the bird translates from Spanish to “Golden pendulum” perhaps because of its yellow tail and and the tree limb swinging mating dance of males (Fendt, 2016). Males weave drooping nests that hang low from trees. The only reference I could find regarding this bird and the Mayans is that Mayan art at Peten depicts the nests of Montezuma Oropendola (Oropendola, Montezuma, 2017).

3. Altamira Oriole (Icterus gularis):

H. Bradford, 2019

H. Bradford, 2019

There are several species of orioles which can be found around the Copan ruins. According to e-bird, these species include Altamira, Streak-backed, Yellow backed, Bar winged oriole, Spot-breasted, Baltimore, and Orchard orioles. The pictured orioles are Altamira Orioles (I believe) since they don’t have streaked backs, spots on their breasts, don’t have a black head like a Baltimore oriole, nor are they as dark as Orchard orioles. Alamira Orioles are found in Central America and range as far north as southern Texas. Like the Montezuma Oropendola, it constructs a long woven nest, which in its case, can reach almost 26 inches in length. The Altamira Oriole was once called the Lichtenstein’s Oriole and Black throated Oriole. It is also the largest New World Oriole (Altamira Oriole Identification, 2017). Yuyum is the lowland Mayan word for oriole and the Bonampak mural depicts a royal figure whose name translates to “Yellow Oriole” or Aj K’an Yuyum, Yellow backed orioles are depicted in the Murals of San Bartolo (Stuart, 2014)

Seeing as there are seven species of orioles in the area and that each are some combination of orange and black, I would advise any newer or intermediate birder like myself to study orioles before visiting. I struggled a bit and probably saw other species, but was too slow to identify or photograph them.

4. Motmots (Momotidae):

Out of Focus Turquoise-browed Motmot, H. Bradford, 2019

One of the most exciting birds that I saw was the Turquoise-browed Motmot. It was a book that I saw in my bird book, so it had captured my imagination before the trip. To suddenly see one and immediately recognize it was amazing! Turquoise-browed Motmots range from southern Mexico to Costa Rica. They can adapt to a number of habitats, but prefer tropical evergreen and tropical deciduous forests. Since it perches on fence posts and wires, it is not too hard to find, and during my trip I saw them several times. Interestingly, the tail feathers are not genetically slender, but get worn down exposing the feather shaft. Turquoise-browed Motmots nest in underground burrows (Streiter, n.d.). Both male and females have long tails, but they use them differently. Both sexes wag their tails to indicate to predators that they have spotted the threat, but males use their tails for sexual displays as well. It is also the national bird of El Salvador and Nicaragua (Turquoise-browed Motmot (Eumomota superciliosa).n.d.)

Hidden and shady view of Lesson’s Motmot

To make matters more confusing, there is actually another species of Motmot that can be found at Copan. Lesson’s Motmot is also found in the area. I spotted one through some dense foliage, so I was unable to get a decent photo. However, the two species are very similar in their plumage as both have bright turquoise brows, green coloration on their bodies, black masks, and racket tails. Despite the poor photo of Lesson’s Motmot, the main difference that I could see between the two is that Lesson’s Motmot does not have the long, featherless shaft that the Turquoise-browed Motmot possess. The featherless area is much shorter. Lesson’s Motmot is also chunkier and longer than the Turquoise-browed Motmot. Both birds were spotted on a trail that cut to the left before the main complex of ruins. One source said that motmots can be found by cenotes, or underground pools. According to Mayan stories, the Motmot was the most beautiful bird, but lost its feathers after a hurricane and went to the cenotes to hide (Robinson, 2013).

5. Toucans (Ramphastidae):

Keel-billed Toucan, H. Bradford 2019

I didn’t actually see these birds at Copan, but nearby at Maccaw Mountain. There are feeding stations for wild birds near the entrance of the rehabilitation center and various wild birds around the parking lot, even though the sanctuary itself features aviaries of mostly rescued animals. The two species of toucans that I saw in this area were a Keel-Billed Toucan and Collared Aracari. E-bird lists these as the only two species of toucans found in the area. The Keel-billed Toucan is identifiable by its colorful green, red, yellow, and turquoise beak, which is why it is sometimes called the Rainbow billed Toucan. They have no known affinity for colorful cereal and instead prefer a diet of fruit and nuts. They are considered common and their populations are listed as Least Concern, though climate change is pushing their range to higher elevations They range from southern Mexico to Northern Colombia, in humid lowland forest canopies (Jones and Griffiths, 2011).

Collared Aracari, H. Bradford 2019

The Collared Aracari is smaller than other toucans in its range and is the northernmost Aracari species. It is black, with yellow underparts, and a reddish color collar. It looks similar to other species of Aracari, but none fall within most of its range. It does overlap with the Fiery Billed Aracari in Panama and Costa Rica. It is primarily a frugavore, but does eat insects, eggs, nestlings, and small vertebrates. It is considered a species of Least Concern, but as a cavity nester it is sensitive to deforestation (Green and Cannan, 2017).

Northern Lacandon Mayan men would give yellow breast feathers from toucans to their wives as a gift. Women tied the feathers into their hair to symbolize marriage. Toucan breast feathers are also featured in the garb of warriors on the Bonampak mural in Chiapas (Nations, 2006). Otherwise, I could not find other references to the importance of toucans to the Mayans. While I don’t have any other Mayan stories, I do have a modern tale of greed. MIA, a California based non-profit concerned with Mayan archaeology and education, was asked to change their logo from a toucan because Kellogg’s believed it was too close to Toucan Sam (Hsu, 2011). Kellogg’s also took issue with the use of Mayan imagery due to similar settings that Toucan Sam appeared in. The non-profit found that the only thing Kellogg’s had connected to Mayan culture was an online game where in Toucan Sam encounters a racialized villain character representing a Mayan (Cushing, 2011). A negative publicity campaign against Kellogg’s resulted in the company paying $100,000 to MAI, removing the online game, and featuring MAI’s website on cereal boxes (Patterson, 2011). The offending logo can be found below:

Clearly this logo is too similar to Toucan Sam…

Clearly this logo is too similar to Toucan Sam…

6. White-throated Magpie-jay (Calocitta formosa)

White-throated Magpie-jays, H. Bradford 2019

I spotted several White-throated Magpie-jays along a trail that leads to the Copan Ruins. They can be found at the forest edges, ranches, and outskirts of towns among the dry tropical forests of the Central Mexico to Costa Rica’s Pacific coast, which is exactly the sort of environment I spotted them in (outside of town, by a pasture for cows). Due to deforestation, their range is expanding southward in Costa Rica, thus they are a bird that actually benefits from human activity and are considered a species of Least Concern. White-throated Magpie-jays feed on both insects (but also eggs and small vertebrates) and fruits, switching their diet depending on if it is the dry or wet season. They are social birds and unique because they form groups organized with a dominant female, her mate, and several female offspring. The adult female offspring assist with feeding the dominant female and her younger offspring. Male birds move between groups, unless the dominant female is nesting. Male magpie jays produce up to sixty vocalizations, which are used to communicate predator threats or the presence of low threat birds. These alarm calls may be used by males to attract the attention of females, which otherwise might not have much use for them (White-throated Magpie-Jay (Calocitta formosa, n.d.)  In general, Magpie-Jays are a genus called Calocitta, which include White Throated Magpie Jays and Black-throated Magpie-jays. The two birds can hybridize and both are known for their long tail length. Jays, or for that matter magpies which they are named after, are corvids or members of the crow family. Members of the crow family are among the smartest birds in the world and some species are known to use tools, play tricks, hold funerals, and teach each other information. Experiments with Eurasian scrub jays conducted by Dr. Nicky Clayton of Cambridge University, using worms and beetles suggest that the birds may be able to consider the preferences of their mate when choosing whether to eat worm or beetle. Her experiments with Western scrub jays demonstrated that the birds were able to remember where and when they had cached food. If a perishable food item such as wax worms had been cached several days prior (and was no longer palatable), the birds went for previously cached peanuts instead. This is despite the fact that the birds prefer waxworms. The jays were also found to be able to plan ahead by caching pine nuts in a room where they regularly found breakfast, so that they would find more food each morning (Balter, 2016). While many corvids cache food, White-throated magpie jays are unusual in that they do not engage in notable caching activity. Corvids are believed to have descended from a moderate caching ancestor. New world jays themselves evolved from a caching corvid. Loss of the ability to cache occurred at least twice independently in corvid evolution as maintaining this ability has a high metabolic cost and requires an enlarged hippocampus (de Kort and Clayton, 2006). Because White-throated magpie-jays do not cache, I will assume they do not have quite the memory capabilities of other jays. Still, they are pretty unique birds in that they have female dominated social groups AND they are unique non-caching jays.

In general, Magpie-Jays are a genus called Calocitta, which include White Throated Magpie Jays and Black-throated Magpie-jays. The two birds can hybridize and both are known for their long tail length. Jays, or for that matter magpies which they are named after, are corvids or members of the crow family. Members of the crow family are among the smartest birds in the world and some species are known to use tools, play tricks, hold funerals, and teach each other information. Experiments with Eurasian scrub jays conducted by Dr. Nicky Clayton of Cambridge University, using worms and beetles suggest that the birds may be able to consider the preferences of their mate when choosing whether to eat worm or beetle. Her experiments with Western scrub jays demonstrated that the birds were able to remember where and when they had cached food. If a perishable food item such as wax worms had been cached several days prior (and was no longer palatable), the birds went for previously cached peanuts instead. This is despite the fact that the birds prefer waxworms. The jays were also found to be able to plan ahead by caching pine nuts in a room where they regularly found breakfast, so that they would find more food each morning (Balter, 2016). While many corvids cache food, White-throated magpie jays are unusual in that they do not engage in notable caching activity. Corvids are believed to have descended from a moderate caching ancestor. New world jays themselves evolved from a caching corvid. Loss of the ability to cache occurred at least twice independently in corvid evolution as maintaining this ability has a high metabolic cost and requires an enlarged hippocampus (de Kort and Clayton, 2006). Because White-throated magpie-jays do not cache, I will assume they do not have quite the memory capabilities of other jays. Still, they are pretty unique birds in that they have female dominated social groups AND they are unique non-caching jays.

I could not find any references to the significance of jays to the Mayans, but other Native American cultures have presented Blue jays as trickster, thief, or bully characters. Cree people envisioned gray jays as benign trickers and its nickname Whisky Jack, may have come from the Algonquin word “Wisakedjak.” In Algonquin stories, Wisakedjak actually describes a trickster crane that let loose a terrible flood (Chadd and Taylor, 2016).

7. Clay Colored Thrush (Turdus grayi):

I saw quite a few of these drab, unassuming birds hidden amongst the forests that shroud the Copan ruins. Yet, oddly enough it is the national bird of Costa Rica. This seems odd considering there are so many colorful, charismatic birds in Central America. It was designated the National Bird of Costa Rica in 1977 because of its song and association with the greening of the season (so perhaps end of dry season?). It is known as Yigüirro in Costa Rica. It eats snails, worms, and insects. It was once named Gray Thrush after a British ornithologist and was also known as the Clay Colored Robin. It is not shy around humans and can live in urban settings. Perhaps because it is common, has a pretty song, and often around humans, in Costa Rican culture it appears in poems, stories, and songs (Javi, 2014). I am not sure what the Mayans thought of this bird, but it is neat that such an ordinary bird has national importance.

8. Turkey (Meleagris):

I saw a turkey at the Copan ruins and wondered what it was doing there. I know that turkeys were domesticated by Native Americans, so I wondered if it was a wild turkey or a domesticated turkey. In this case, it was a domesticated turkey. Turkey bones have been found at Mayan archaeological site in Guatemala dating from between 300 BC and 100 AD. The species of turkey found at the site actually originated in Mexico, where all domestic turkeys are from. So, it means that Mayans imported turkeys from outside of their homelands to be kept or raised (University of Florida, 2012). Originally, turkeys were domesticated for their feathers, which were used in ceremonies, robes, and blankets. In Mexico, they were domesticated in 800 BC and in Southwest United States this occurred in 200 BC. (Viegas, 2010) Both Anasazi and Aztecs domesticated turkeys. Anasazi domesticated turkeys from Rio Grand and Eastern subspecies and the Aztecs from a vanished southern Mexican subspecies. The Anasazi domestic turkey has disappeared from history (Smith, 2017). All modern domesticated turkeys are from Aztec domesticated turkeys (Viegas, 2010) While a person can’t include domesticated turkeys on their birding list, they are still beautiful birds with a lot of Mesoamerican history.

Conclusion:

There were many other birds that I saw at Copan as well, including summer tanagers, golden fronted woodpeckers, rufous naped wren, black vultures, and more! So, this overview is not comprehensive of the birds that I saw. It also doesn’t include many other birds that were important to the Mayans. For instance, water birds were actually surprisingly prominent in Mayan art. Over 52% of natural bird species depicted in Mayan art are water birds such as herons, egrets, and cormorants. Of these depictions, 83% are from the Late Classic period, which was associated with drought (Stuart, 2015). The Copan ruins are near the Copan River, so it is possible that a person could see some water birds if they were near the river. Another bird that was important to the Mayans are Resplendent Quetzals. Resplendent Quetzals can be found at elevations between 1000 to 3300 m and prefer evergreen cloud forests with plentiful fruit trees, where they forage from the canopy. They are considered Near Threatened, since they are sensitive to deforestation and climate change. Copan situated in a valley at 700 m above sea level, so, the elevation is not suitable for Quetzals. According to E-bird, there have been some Resplendent Quetzal sightings at Finca El Cisne and the aptly named Montana El Quetzal, which are not far from Copan, but even these sightings are infrequent. Both Mayans and Aztecs revered the bird as a figure representing goodness and light, and as a deity of air. Its name comes from Nahuatl and the Mayan word for the bird is Kuk. Quetzal feathers were reserved for royalty and priests and more valuable than gold or jade. The birds were captured, their feathers plucked, and then released, as it was believed that the birds would die in captivity. Aztecs associated the bird with Quetzalcoatl. Today, the bird is featured on Guatemala’s coat of arms, flag, and currency (which is called quetzal). Although they are not at Copan, I figured it was worth a mention due to their cultural importance. With that said, the Copan ruins are a great place to enjoy nature. Since nature is as much a part of the history of the Mayans as the Copan ruins, a person shouldn’t feel guilty if they find themselves admiring the plants, birds, or butterflies instead of the city of stone. These things are all connected.

Sources:

Altamira Oriole Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Altamira_Oriole/id

Balter, M. (2016, July 22). Meet the Bird Brainiacs: Eurasian Jay. Retrieved from https://www.audubon.org/magazine/march-april-2016/meet-bird-brainiacs-eurasian-jay

Chadd, R. W., & Taylor, M. (2016). Birds: Myth, lore & legend. London, UK: Bloomsbury Natural History, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Cushing, T. (2011, September 8). Kellogg’s Stakes Claim To Toucans, Mayan Imagery; Issues Cease-and-Desist To Guatemalan Non-Profit. Retrieved from https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20110907/15550615845/kelloggs-stakes-claim-to-toucans-mayan-imagery-issues-cease-and-desist-to-guatemalan-non-profit.shtml

de Kort, S. R., & Clayton, N. S. (2006). An evolutionary perspective on caching by corvids. Proceedings. Biological sciences, 273(1585), 417–423. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3350

Fendt, L. (2016, March 01). 6 Costa Rican animal names decoded. Retrieved from https://www.caminotravel.com/6-costa-rican-animal-names-decoded/

Green, C. and R. Kannan (2017). Collared Aracari (Pteroglossus torquatus), version 1.0. In Neotropical Birds Online (T. S. Schulenberg, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/nb.colara1.01

Greshko, M. (2018, August 13). Early Native Americans Imported Exotic Parrots, DNA Reveals. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2018/08/news-ancient-dna-chaco-canyon-pueblo-macaws-archaeology/

Hellmuth, N. (2015, September 06). Macaws and Parrots in 3rd-9th Century Mayan Art. Retrieved from http://www.revuemag.com/2011/04/macaws-and-parrots-in-3rd-9th-century-mayan-art/

Helmke, C., & Nielsen, J. (2015). The Defeat of the Great Bird in Myth and Royal Pageantry: A Mesoamerican Myth in a Comparative Perspective. Comparative Mythology, 1, 23-60.

Hsu, T. (2011). Mayan group’s logo too much like Toucan Sam, Kellogg’s squawks. Retrieved from https://latimesblogs.latimes.com/money_co/2011/08/kellogg-asks-mayan-group-to-remove-toucan-from-logo.html

Iconography, characteristics of painted macaws on Early Classic, Tzakol, basal flange bowls. (2014, October). Retrieved from http://www.maya-archaeology.org/neotropical-Mayan-ethnozoology-sacred-utilitarian-animals-reptiles-fish-birds-insects-iconography-epigraphy-faunal-remains/Mayan-iconography-scarlet-macaws-Tzakol-Early-Classic-bird-images.php

Javi. (2014, January 23). History of the national bird: Clay-colored thrush (Yigüirro). Retrieved from https://www.govisitcostarica.com/blog/post/history-of-the-national-bird-clay-colored-thrush.aspx

Jones, R. and C. S. Griffiths (2011). Keel-billed Toucan (Ramphastos sulfuratus), version 1.0. In Neotropical Birds Online (T. S. Schulenberg, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/nb.kebtou1.01

Nations, J. D. (2006). “Maya Tropical Forest: People, Parks, and Ancient Cities”.

Oropendula, Montezuma. (2017, February). Retrieved from https://www.maya-ethnozoology.org/images-birds-species-bird-watchers-guatemala-mexico-belize-honduras/montezuma-oropendola-psarocolius-wagleri-bird-nests-peten-izabal-guatemala.php

Patterson, R. (2011, November 18). Kellogg Reaches Settlement in ‘Toucan’ Trademark Dispute – Few Feathers Ruffled. Retrieved from http://www.ipbrief.net/2011/11/17/kellogg-reaches-settlement-in-toucan-trademark-dispute-–-few-feathers-ruffled/

Robinson, J. K. (2013, July 23). Land of the Maya the way it was then. Retrieved from https://www.sfgate.com/travel/article/Land-of-the-Maya-the-way-it-was-then-4003689.php

Sample, R. and R. Kannan (2016). Montezuma Oropendola (Psarocolius montezuma), version 1.0. In Neotropical Birds Online (T. S. Schulenberg, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/nb.monoro1.01

Smith, J. (2017, November 17). Tracing the Wild Origins of the Domestic Turkey. Retrieved from https://blog.nature.org/science/2017/11/20/tracing-the-wild-origins-of-the-domestic-turkey/

Streiter, A. (n.d.). Turquoise-browed Motmot, Costa Rica. Retrieved from https://www.anywhere.com/flora-fauna/bird/turquoise-browed-motmot

Stuart, P. (2015). Birds and environmental change in the Maya area (Unpublished master’s thesis). A Division III examination in the School of Natural Science, Hampshire College, May 2015. Chairpersons, Alan Goodman and Brian Schultz.

Stuart, D. (2014, April 20). A Glyph for Yuyum, “Oriole,” in a Name at Bonampak. Retrieved from https://decipherment.wordpress.com/2014/04/17/a-glyph-for-yuyum-oriole-in-a-name-at-bonampak/

Turquoise-browed Motmot (Eumomota superciliosa). (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/2168-Eumomota-superciliosa

University of Florida. “Earliest use of Mexican turkeys by ancient Maya.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 9 August 2012. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/08/120809090706.htm>.

Viegas, J. (2010, February 01). Native Americans tamed turkeys in 800 B.C. Retrieved from http://www.nbcnews.com/id/35186605/ns/technology_and_science-science/t/native-americans-tamed-turkeys-bc/#.XOPizqR7mUk

White-throated Magpie-Jay (Calocitta formosa), In Neotropical Birds Online (T. S. Schulenberg, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. retrieved from Neotropical Birds Online: https://neotropical.birds.cornell.edu/Species-Account/nb/species/wtmjay1

Whitely, D. (2015, March 07). How the scarlet macaw returned to Copán, Honduras. Retrieved from http://www.grumpytraveller.com/2015/03/07/how-the-scarlet-macaw-returned-to-copan-honduras/

Posted in

birding,

culture,

history,

outdoors,

travel and tagged

Altimira Oriole,

birds,

Clay colored thrush,

collared aracari,

Copan birds,

Copan nature,

Copan ruins,

H. Bradford,

Heather Bradford,

Honduras birds,

jay intelligence,

keel-billed toucan,

Kellogg's lawsuit,

magpie jay,

Mayan birds,

Mayan culture,

Montezuma Oropendola,

Motmot,

oriole,

Popol Vuh,

Quetzal,

Scarlet Macaw,

Seven Macaw,

toucan,

toucans,

travel,

Turkey,

turkey domestication,

Turquoise-browed motmot,

White-throated Magpie-jay |

A replica of a ballcourt decoration at Copan representing Seven Macaw, (Museum of Mayan Sculpture, Copan, Honduras). Photo by Mark Cartwright, 2014

A replica of a ballcourt decoration at Copan representing Seven Macaw, (Museum of Mayan Sculpture, Copan, Honduras). Photo by Mark Cartwright, 2014

Clearly this logo is too similar to Toucan Sam…

Clearly this logo is too similar to Toucan Sam…

In general, Magpie-Jays are a genus called Calocitta, which include White Throated Magpie Jays and Black-throated Magpie-jays. The two birds can hybridize and both are known for their long tail length. Jays, or for that matter magpies which they are named after, are corvids or members of the crow family. Members of the crow family are among the smartest birds in the world and some species are known to use tools, play tricks, hold funerals, and teach each other information. Experiments with Eurasian scrub jays conducted by Dr. Nicky Clayton of Cambridge University, using worms and beetles suggest that the birds may be able to consider the preferences of their mate when choosing whether to eat worm or beetle. Her experiments with Western scrub jays demonstrated that the birds were able to remember where and when they had cached food. If a perishable food item such as wax worms had been cached several days prior (and was no longer palatable), the birds went for previously cached peanuts instead. This is despite the fact that the birds prefer waxworms. The jays were also found to be able to plan ahead by caching pine nuts in a room where they regularly found breakfast, so that they would find more food each morning (Balter, 2016). While many corvids cache food, White-throated magpie jays are unusual in that they do not engage in notable caching activity. Corvids are believed to have descended from a moderate caching ancestor. New world jays themselves evolved from a caching corvid. Loss of the ability to cache occurred at least twice independently in corvid evolution as maintaining this ability has a high metabolic cost and requires an enlarged hippocampus (de Kort and Clayton, 2006). Because White-throated magpie-jays do not cache, I will assume they do not have quite the memory capabilities of other jays. Still, they are pretty unique birds in that they have female dominated social groups AND they are unique non-caching jays.

In general, Magpie-Jays are a genus called Calocitta, which include White Throated Magpie Jays and Black-throated Magpie-jays. The two birds can hybridize and both are known for their long tail length. Jays, or for that matter magpies which they are named after, are corvids or members of the crow family. Members of the crow family are among the smartest birds in the world and some species are known to use tools, play tricks, hold funerals, and teach each other information. Experiments with Eurasian scrub jays conducted by Dr. Nicky Clayton of Cambridge University, using worms and beetles suggest that the birds may be able to consider the preferences of their mate when choosing whether to eat worm or beetle. Her experiments with Western scrub jays demonstrated that the birds were able to remember where and when they had cached food. If a perishable food item such as wax worms had been cached several days prior (and was no longer palatable), the birds went for previously cached peanuts instead. This is despite the fact that the birds prefer waxworms. The jays were also found to be able to plan ahead by caching pine nuts in a room where they regularly found breakfast, so that they would find more food each morning (Balter, 2016). While many corvids cache food, White-throated magpie jays are unusual in that they do not engage in notable caching activity. Corvids are believed to have descended from a moderate caching ancestor. New world jays themselves evolved from a caching corvid. Loss of the ability to cache occurred at least twice independently in corvid evolution as maintaining this ability has a high metabolic cost and requires an enlarged hippocampus (de Kort and Clayton, 2006). Because White-throated magpie-jays do not cache, I will assume they do not have quite the memory capabilities of other jays. Still, they are pretty unique birds in that they have female dominated social groups AND they are unique non-caching jays.

![2[1]](https://brokenwallsandnarratives.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/21.png?w=492&h=412)

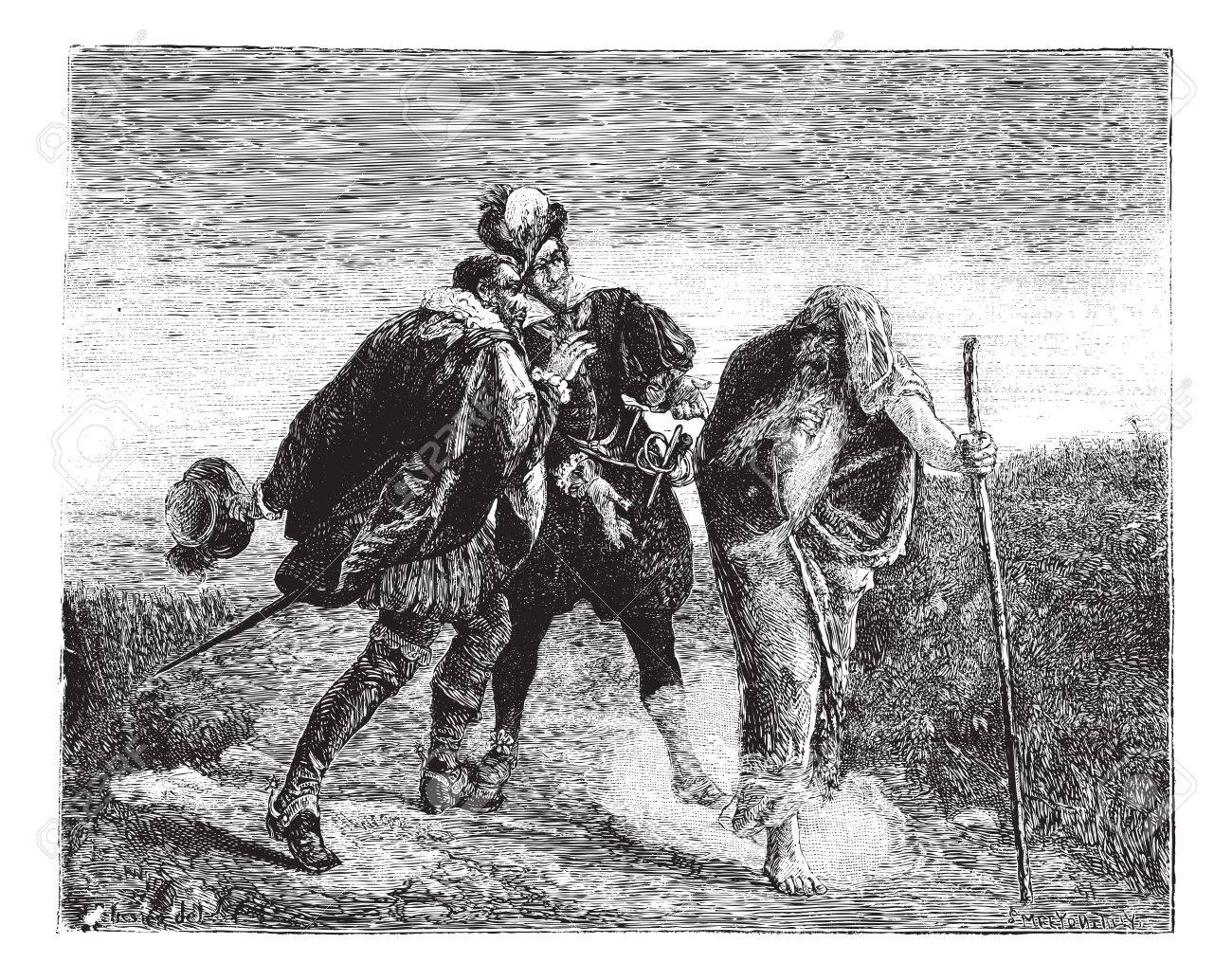

The term Wandering Jew comes from 13th Century Christian folklore. The character is a Jewish man who was said to have taunted Jesus before he was crucified. As punishment for his taunt, he was cursed to walk the Earth until the return of Christ. In some stories, his clothes and shoes never wear out and after 100 years, he returns to being a younger man. He was a perpetual traveler, unable to rest, but able to converse in all of the languages of the world. This is not based on any actual Biblical story, though it may have been inspired by the story of Caine and European paganism. Much like Big Foot or ghosts today, Europeans of the time believed that they had actually seen this character. For hundreds of year, even into the present day, this character has appeared in literature and art.

The term Wandering Jew comes from 13th Century Christian folklore. The character is a Jewish man who was said to have taunted Jesus before he was crucified. As punishment for his taunt, he was cursed to walk the Earth until the return of Christ. In some stories, his clothes and shoes never wear out and after 100 years, he returns to being a younger man. He was a perpetual traveler, unable to rest, but able to converse in all of the languages of the world. This is not based on any actual Biblical story, though it may have been inspired by the story of Caine and European paganism. Much like Big Foot or ghosts today, Europeans of the time believed that they had actually seen this character. For hundreds of year, even into the present day, this character has appeared in literature and art.

African Americans came to the United States as slaves and were only allowed to grow a small selection of vegetables for themselves. Collards were one of them. While the vegetable is not African in origin, the methods of preparation were. West Africans use hundreds of species of leafy greens and prepare them in ways that maintain their high nutrient content. Enslaved Africans found fewer wild greens here and came to rely on collards, which were brought here by the British. (Depending upon where the slaves were taken from, they may have been familiar with leafy cabbages as in the Middle Ages, cabbages of various sorts were traded into Africa through Morocco and Mali). They are unique among cabbages in that they can continue to produce leaves over their growing season. They can be harvested for months when other vegetables quit in the cold weather. Collards helped slaves to survive due to their productivity. For this reason, poor white people also grew collards. It is a cheap, productive, healthy plant. Although white Southerners grew the plant, it was a marginal crop to European settlers and African Americans deserve credit for popularizing the use of greens and their preparation.

African Americans came to the United States as slaves and were only allowed to grow a small selection of vegetables for themselves. Collards were one of them. While the vegetable is not African in origin, the methods of preparation were. West Africans use hundreds of species of leafy greens and prepare them in ways that maintain their high nutrient content. Enslaved Africans found fewer wild greens here and came to rely on collards, which were brought here by the British. (Depending upon where the slaves were taken from, they may have been familiar with leafy cabbages as in the Middle Ages, cabbages of various sorts were traded into Africa through Morocco and Mali). They are unique among cabbages in that they can continue to produce leaves over their growing season. They can be harvested for months when other vegetables quit in the cold weather. Collards helped slaves to survive due to their productivity. For this reason, poor white people also grew collards. It is a cheap, productive, healthy plant. Although white Southerners grew the plant, it was a marginal crop to European settlers and African Americans deserve credit for popularizing the use of greens and their preparation.

While the name might suggest that the seed came from Nigeria or Niger, nyjer seed actually comes from the Guizotia abyssinica plant which grows in the highlands of Ethiopia. I found a reference to the seed being called Nigerian thistle, which to me indicates that whomever named the seed must have had some confusion about the geography of Africa or, perhaps generically called it “niger” seed as a stand in for Africa itself. Nigeria, Niger, and the Niger River are all located in West Africa whereas Ethiopia is in East Africa. The genus Guizotia contains six species, of which five are native to Ethiopia. A distribution map of the species shows that it grows naturally in some areas of Uganda, Malawi, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sudan. It also grows in India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Nepal. The plants found in and around India are believed to have been brought there long ago by Ethiopian migrants, who also brought millet to the region. Therefore, Nyger seed really has nothing to do with the countries of its (former) namesake and represents a sort of “imagined Africa” rather than any geographical or botanical reality.

While the name might suggest that the seed came from Nigeria or Niger, nyjer seed actually comes from the Guizotia abyssinica plant which grows in the highlands of Ethiopia. I found a reference to the seed being called Nigerian thistle, which to me indicates that whomever named the seed must have had some confusion about the geography of Africa or, perhaps generically called it “niger” seed as a stand in for Africa itself. Nigeria, Niger, and the Niger River are all located in West Africa whereas Ethiopia is in East Africa. The genus Guizotia contains six species, of which five are native to Ethiopia. A distribution map of the species shows that it grows naturally in some areas of Uganda, Malawi, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sudan. It also grows in India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Nepal. The plants found in and around India are believed to have been brought there long ago by Ethiopian migrants, who also brought millet to the region. Therefore, Nyger seed really has nothing to do with the countries of its (former) namesake and represents a sort of “imagined Africa” rather than any geographical or botanical reality.