Lessons from World War I

Lessons from World War I

H. Bradford

11/12/18

November 11, 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I. This is a momentous anniversary since our world is still deeply influenced by the outcome of World War I. Yet, in the United States, World War I is not a popular war to learn about. It is not a war that American students love to learn about in the same way the they love World War II, with its villains and seemingly black and white struggle against fascism. Despite its impact on world history, it does not lend itself as many movies and documentaries. When it does, for instance in the popular Wonder Woman film released in 2017, it is warped to resemble World War II to make itself more interesting to American audiences. Of course, World War I is important in its own right and offers important historical lessons. As an activist, it is useful to examine the struggle against World War I, as it was a crucible that tested the ideological mettle of revolutionaries and activists.

World War I- An Introduction

World War I is significant for its brutality, industrialized warfare, and for reshaping the globe. The brutality of the war is massive stain on the blood soaked histories of all imperialist nations. As a low estimate, over 8.5 million combatants died in the war with 21 million wounded and up to 13 million civilian casualties. The nations that went to war were criminal in their barbaric sacrifice of millions of soldiers. For instance, the Russian Empire sent troops into battle armed only with axes, no wire cutters, and without boots. Early in the war, of an army corps of 25,000 soldiers, only one returned to Russia, as the rest were either killed or taken prisoner. In the first month of the war alone, 310,000 Russians were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner. On several occasions, British soldiers were ordered to advance against German trenches, which only resulted in massive bloodshed as they faced machine gun fire and tangled miles of barbed wire fences. When forced to march against the trenches at Loos, 8,000 of 10,000 British soldiers were killed for a gain of less than two miles of occupied territory. In the first two years of the war, Britain had 250,000 dead soldiers for the gain of eight square miles. At the Battle of Verdun, 90,000 British soldiers perished in six weeks. At the Battle of Somme, 57,000 British troops perished in one day and 19,000 in one hour alone. The fighting continued even after the Armistice was signed on 11/11/18, as it was signed at 5 am, but did not go into effect until 11 am. In the twilight between war and peace, 2,738 soldiers died and 8,000 were wounded. The scope of this senseless bloodshed seems unfathomable. The scale of human suffering was magnified by industrial methods of war. World War I saw new weapons, such as tanks, airplanes, giant guns mounted on trains, machine guns (which had been used in previous conflicts such as the Boer war), aerial bombings from zeppelins, submarines, and poison gas. Barbed wire was also a recent invention, which secured the defensive lines of both sides, ensuring a bloody stalemate. The conflict itself resulted in the collapse of empires and the division of colonial spoils (Hochschild, 2011).

Almost everyone who has taken a history class remembers the tired narrative that World War I began in June 1914 with the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand and his pregnant wife, Sofia in Sarajevo by the Bosnian Serb, Gavrilo Princip. This unleashed a chain of events wherein Russia vowed to protect Serbia against an Austro-Hungarian invasion. In turn, Austro-Hungary sought to ally itself with Germany against Russia and France vowed to ally itself with Russia against Germany. Britain justified entering the war on behalf of poor, innocent, neutral, little Belgium (which just years prior was neither poor, innocent, or neutral in King Leopold II’s genocidal rubber extraction from the Congo Free State), a strategic passage for German troops invading France. The narrative goes that World War I was born from the anarchy of alliances. Of course, the causes of the war are far more profound than upkeeping treaties and national friendships. This method of framing the war as a domino of effect treaties renders the possibility of resisting the war invisible. It also ignores that these treaties themselves were the outcome of imperialist countries volleying for power.

For historical context, there were massive changes in Europe during the 1800s. On one hand, the 1800s saw the accelerating decline of the Ottoman Empire, which had been considered the sickman of Europe in terms of empires since it lost at the Battle of Vienna in 1683. Wars and independence movements of the 1800s shrank Ottoman territory as countries such as Greece, Serbia, Egypt, Bulgaria, and later Albania, became independent. The Ottoman Empire was strained by internal debate over modernizing or harkening back to bygone times. The century saw the disbanding of the Janissaries, defeat in the Russo-Turkish war, and the revolt of the Young Turks. The Russo-Turkish War saw the establishment of independent Serbia, Romania, and Bulgaria. The Treaty of Berlin awarded Bosnia to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which upset Serbians and inspired the formation of the Black Hand, which fought for reunification with Bosnia as well as unification with other areas populated by Serbians. The disintegration of the Ottoman Empire created territorial concerns as newly emerging countries such as Serbia, Bulgaria, and Albania sought to establish boundaries at the expense of one another. The Balkan Wars fought just prior to the start of WWI came out of these territorial disputes. Thus, the Ottoman entry into WWI on the side of Germany and Austro-Hungary was largely in the interest of retaking lost territories. Likewise, Bulgaria joined the conflict on the side of the Central Powers with the hope of regaining territory lost in the 1913 Balkan War, namely southern Macedonia and Greece (Jankowski, 2013).

While Ottomans were in decline, Germany and Russia were struggling for ascendancy. The 1800s saw the formation of the German state, an outcome of the 1866 war between Prussia and Austro-Hungary and the Germanification of people within this territory under Kaiser Wilhelm II. The 1800s also saw Germany’s entry into the imperialist conquest of the world as it sought to colonize places such as modern day Namibia, Botswana, Cameroon, Rwanda, Burundi, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Marshall Islands, etc (Jankowski, 2013). It should also be noted that Germany was 50% larger than its present size with one of Europe’s strongest economies (Hochschild, 2011). The Russian Empire saw its own economy growing with the expansion of railroads and a population twice the size of Germany’s (Hochschild, 2011). Although Russia was hobbled in the 19th century by serfdom and slow industrialization, it won the Russo-Turkish War only to see its gains reversed by the Treaty of Berlin. It was further humiliated by the loss of a 1905 war against Japan and held on to brutal Tsarist autocracy at the cost of hundreds of lives in the face of protests for bread and labor reforms that same year. The 1800s was also a time of Russian imperial expansion into Central Asia and the Caucasus, with interest in expansion as far as India, much to the chagrin of Britain. After losing the 1905 war with Japan, Russia began to expand and modernize its military, which led to Germany doing the same for fear of being eclipsed (Jankowski, 2013). This drive for global conquest and for gobbling up the shrinking territories is again related to imperialism.

German colonies at the turn of the century

Prior to the outbreak of World War I, European powers expected that war was inevitable. British and French officials were expecting Germany to go to war with Russia after Russia’s 1905 uprising. In 1894, France and Russia entered an alliance with one another that if one was attacked by Germany, the other would declare war on Germany to ensure a war on two fronts. France had lost territory (Alsace and Lorraine) in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, so there was a strong desire for revenge among nationalists who wanted to go to war with Germany to reclaim lost land (Tuchman, 1990). Between 1908 and 1913, the arms expenses of the six largest countries of Europe increased by 50% and 5-6% of national budgets were devoted to military spending (Hochschild, 2011). For nine years, Britain and France strategized what a German attack would look like and duly prepared. Belgian had been created as a neutral state in 1830 with Britain a strong proponent of neutrality to secure itself from invasion. In 1913, Germans helped to reorganize the Ottoman Army, which upset Russia. France and Germany had each developed their own war plans, such as France’s Plan 17 and Germany’s Schlieffen Plan (Tuchman, 1990). Even in popular culture in the years leading up to the war, German invasion became a fiction genre. For example, the Daily Mail ran a novel called The Invasion of 1910, which depicted a German invasion of the East coast of England (Hochschild, 2011).

WWI and Imperialism

From a Marxist perspective, the primary cause of World War I was imperialism. Imperialism was the linchpin of the anti-war socialist analysis of World War I, a topic which we be explored in greater detail in the next section. The main proponent of this perspective was Vladimir Lenin, who drew his analysis of imperialism from the writings of Rosa Luxemburg, who wrote The Accumulation of Capital and Nikolai Bukharin, who wrote Imperialism and the World Economy. Lenin also developed his theory based upon economist John Hobson’s Imperialism: A Study and Marxist economist Rudolf Hilferding’s Financial Capital (Nation, 1989). According to Lenin, imperialism was the highest stage of capitalism, characterized by such things as monopoly capital, a monopoly of large banks and financial institutions, the territorial partition of the world, the economic partition of the world by cartels, and the control of raw materials by trusts and the financial oligarchy. Lenin characterized imperialism resulting from a trend towards the concentration of productive power. That is, imperialism features fewer companies with larger worker forces and greater production. To him, the movement towards the monopolization of capital occurred following a series of economic crises in capitalism in 1873 and 1900 (2005) The fusion of capital into larger blocs was an important characteristic of capitalism observed by Karl Marx. It occurred when larger capitalists destroying smaller ones and through the union of smaller capital into larger ones, a process mediated by banks and stock markets. Once there were fewer firms on the playing field, they often united into cartels or agreements to limit competition and divide the market. Banks also became concentrated into fewer powerful banks, which melded with industrial capital and the state (Patniak, 2014). On one hand, imperialism provided the advantage that it increased economic organization, planning, and efficiency, which were economic characteristics that Lenin theorized might serve a transition to socialism. On the other hand, imperialism also resulted in less innovation, stagnation, and an unevenness in concentrations of capital. This unevenness created contradictions in the development of cities versus rural areas, heavy versus light industry, gaps between rich and poor, and gaps between colonies and colonizers. These contradictions created systemic instability in the long run, which cartels could only temporarily stave off (Nation, 1989).

Imperialism resulted in increased competition of state supported monopolies for markets and raw materials. World War I was the result of partitioning the world. In this context, workers were given the choice between fighting for their own national monopolies or making revolution. Lenin believed that workers should turn imperialist war into a civil war against capitalism. This was in contrast to social democrats who wanted workers to fight for their nations or Kautsky who felt workers should defend their nations, but not fight on the offensive. Kautsky had postulated that the world was in a state of ultra imperialism, which would actually result in greater peace and stability as the stakes of war were higher. Rosa Luxemburg believed that capitalism had not yet reached every corner of the globe, so revolution was not yet possible. Thus, there was debate over the nature of imperialism within the socialist movement. To Lenin, imperialism allowed the prospect of revolution in both advanced and colonized countries, since colonized countries were brought into imperialist wars as soldiers (Nation, 1989). For instance, 400,000 African forced laborers died in the war for Great Britain. The first use of poison gas in the war was in April 1915 and the first victims were French troops from North Africa who observed the greenish yellow mist of chlorine, then succumbed to coughing blood and suffocation. Although the horror of zeppelin bombs fell on Britain in May 1915, the first use of zeppelin bombings was actually by Spain and France before the war, to punish Moroccans for uprising. And while Britain justified the war as a matter of self-determination for Belgium, they crushed self-determination for Ireland when 1,750 Irish nationalists rose up in 1916 for independence. Britain sent troops there, eventually out numbering the nationalists 20 to 1. Fifteen of leaders of the uprising were shot, including James Connolly who was already wounded when executed and had to be tied to a chair to be shot (Hochschild, 2011). Further, while the European arena is given more historical attention, battles were fought in colonies as well. In 1916 in south-west Tanzania, Germany fought the the British with an army of about 15,000. Of this number, 12,000 were Africans- who fought other Africans fighting on behalf of the British. Because the borders were created by Europeans and did not represent cultural, historical, or tribal lands, these African soldiers sometimes had to fight members of their family. More than one million East Africans died in World War I (Masebo, 2015). France enlisted 200,000 West Africans to fight on their behalf in the war, calling them Senegalese tirailleurs, even though they came from various West African countries. These soldiers were forcibly recruited, then promised benefits that they were later denied (AFP, 2018). Colonies were inextricably linked, economically and militarily, to imperialist war efforts. Thus, in addition to blaming imperialism for the outbreak of World War I, Lenin postulated that the national struggle of oppressed nationalities was part of the larger struggle against imperialism.

From Forgotten African Battlefields of WWI, CNN

Lenin noted that by 1900, 90% of African territory was controlled by European powers, in contrast to just over 10% in 1876. Polynesia was 98% controlled by European powers compared to 56% in 1876. As of 1900, the world was almost entirely divided between major European powers with the only possibility of redivision. Between 1884 and 1900, France, Britain, Belgium, Portugal, and Germany saw accelerated expansion of their overseas territories. He quoted Cecil Rhode, who saw imperialism as necessary for creating markets for goods and opportunities for surplus British population (Lenin, 2005). By the time World War I began, the banqueting table of capitalists was full. World War I was a means to redistribute these imperialist spoils. Germany sought to test its power against that of Britain and France. To Lenin, one side or the other had to relinquish colonies (Lenin, War and Revolution, 2005). Indeed, World War I resulted in a re-division of the world. The war saw the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, whose territories were divided among the victors. For instance, Syria and Lebanon became French protectorates and Britain took control of Mesopotamia, most of the Arabian peninsula, and Palestine. The United States, a latecomer to the war, cemented its position as a world power. The defeat of Germany resulted in the redistribution of German colonies, such as German East Africa to Britain, part of Mozambique to Portugal, the division of Cameroon between British and French, and the formation of Ghana and Togo under British and French control, respectively. Even New Zealand and Australia gained control of German Pacific island territories German Samoa, German New Guinea, and Nauru. Various states came out of the defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire, including Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, The Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and the Kingdom of Romania. Of course, revolution destroyed the Russian Empire before the conclusion of the war, resulting in the independence of Finland, Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia. Poland was constructed of territories lost by Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian Empires.

Socialist Resistance to World War I

Like all wars, there was resistance to World War I. A group that would have been well positioned to resist the outbreak of the war was the socialist movement. However, in August 1914, various socialists in Britain, France, Germany, and Austro-Hungary sided with their national governments in participating in World War I (Partington, 2013). For some context, the Second International was a loose federation of socialist groups which arose out of the collapse of the First International in 1876 over debates related to anarchy led by Bukharin. Between its founding in 1889 to the outbreak of World War I, the Second International saw success in terms of rising standards of living for workers, mass popularity, and electoral success that brought socialists into various governments. One the eve of the war, there were three million socialist party members in Germany, one million in France, and a half million in Great Britain and Austria-Hungary respectively (Nation, 1989). The German Socialist Party was the largest party in the the German legislature. Even in the United States, where socialism was less popular, socialist candidate Eugene Debs garnered 900,000 votes in his 1912 presidential bid (Hochschild, 2011). During this time period, socialists of the Second International certainly had opportunities to debate war, as there was the Balkan Wars, Boer Wars, Italy’s invasion of Libya, and war between Russia and Japan. However, the international failed to develop a cohesive anti-war strategy. As World War I approached, socialists made some efforts to organize against it. For instance, in July 1914 socialists organized modest anti-war protests and there were strikes in St. Petersburg (Nation, 1989) and strikes involving over a million workers in Russia earlier in the year. In July 1914, socialist leaders such as Kerrie Hardie, the working class Scottish socialist parliamentarian from Great Britain, Jean Jaures, the French historian and parliamentarian from the French Section of the Workers International, and Rosa Luxemburg, the Jewish Polish Marxist theorist from the German Socialist Party (SPD), met in Brussels for a Socialist Conference to discuss the impending war. Hardie vowed to call for a general strike should Britain enter a war. Jaures spoke before 7,000 Belgian workers calling for a war on war. Unfortunately, Jaures was assassinated in Paris shortly after this meeting by a nationalist zealot. Nevertheless, there were trade union and leftist organized marches in Trafalgar Square in London against the war, where Hardie again called for a general strike against war (Hochschild, 2011). Despite these agitational efforts, the fate of the international was sealed when on August 4th the German SPD voted for emergency war allocations. Socialists in other European countries followed suit, adopted a “defensist” position in which they opted to suspend class struggle in the interest of defending their nations (Nation, 1989). Only 14 of 111 SPD deputies voted against war allocations (Hoschild, 2011). The fact that the majority of socialists supported the war shattered The Second International, which over the course of the war saw the decline of socialist party membership. For instance, Germany’s SPD lost 63% of its membership between 1914-1916 (Nation, 1989). With millions of members in all of the belligerent countries, positions of political power, and union support, socialists had the power to stop the war. Putting nationalism before internationalism was one of the greatest failures of socialists.

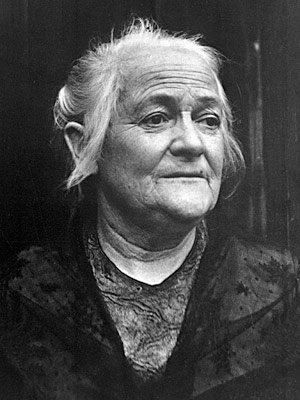

Rosa Luxemburg

Not all socialists agreed with the defensist position and during the course of the war they formed an small opposition within the Second International, a segment of which would eventually became the Third International and Communist Party. This opposition had diverse views, ranging from the Menshevik position that socialists should call for neither victory nor defeat of imperialist powers to Lenin’s position of revolutionary defeatism. As her SPD counterparts were calling for war allocations, Rosa Luxemburg called a meeting at her apartment to oppose the war and strategize how to shore up an anti-war opposition within the party. After this meeting, Karl Liebknecht campaigned around Europe with the slogans that “The Main Enemy is at Home”, “Civil War Not Civil Truce” and echoing Jaures, a call to “Wage War Against War.” They shared a further left position in the party that the only way to end the war was to make revolution. However, both Luxemburg and Liebknecht were arrested in February 1915 (Nation, 1989).

Another early mobilization of socialists against the war was a Women’s International Conference first proposed by Inessa Armand, representing the left faction of the anti-war socialists and organized by Clara Zetkin, who was a centrist within the anti-defensist opposition. Zetkin’s centrist anti-defensist position emphasized peace over making revolution (Nation, 1989). After writing An appeal to Socialist Women of All Countries, Zetkin organized the March 1915 Women’s International Conference in neutral Berne, Switzerland for anti-war socialist women. Although she was not as quick to place blame on the socialists for supporting their governments nor emphasize the need for revolution, Clara Zetkin had a long history of anti-war credentials. She was the secretary of the Women’s Socialist International and which she founded in 1907. She was also one of the founders of International Women’s Day. She was a vocal opponent of British war against Boers in South Africa, articulating this position on a May Day speech in 1900. Later, she was an opponent of the First Balkan War and warned that it could develop into a war between greater European powers (Partington, 2013).

Clara Zetkin

The Women’s International Conference was attended by 28 delegates from 8 countries, who developed resolutions on such things as an immediate end to the war, peace without humiliating conditions on any nation, and reparations for Belgium. A manifesto based upon the conference was published later in June. Again, slogans such as “war on war” and “peace without conquest or annexations” were called for. The role of financial interests such as the arms industry was spotlighted as well as how capitalists used patriotism to dupe workers into fighting in the war and weakening socialism. Russian delegates voted to amend this resolution to clearly blame socialists who had collaborated with capitalist governments and called for women to join illegal revolutionary association to advance the overthrow of capitalism. This amendment was rejected as it was viewed as divisive and called for illegal activity. The British delegation added a amendment that condemned price increases and wage decreases during the war and which welcomed other anti-war activists to join them in struggle. The second part of this resolution was not passed (Partington, 2013). The conference was significant because it was the first anti-war conference attended by representatives from belligerent nations. The conference also set the stage for the Zimmerwald conference, which sought to better organize the opposition within the Second International towards ending the war, reforming the international, or abandoning it (Nation, 1989).

The Zimmerwald Conference began on September 11, 1915 in a small swiss village of Zimmerwald under the auspices that it was the meeting of an Ornithological Society. The conference was attended by 38 individuals from 11 countries. The conference is more famous for its male attendees such as Trotsky, Lenin, Zinoviev, Radek, and Martov. However, several women attended including Henriette Roland-Holst a poet and Social Democratic Party member from the Netherlands, Angelica Balanoff of the Italian Socialist Party, Bertha Thalheimer and Minna Reichert of the SPD in Germany. Henriette Roland-Holst went on to oversee the creation of Der Verbote, a journal which served as a mouthpiece for the ideas of the conference. Clara Zetkin and Rosa Luxemburg were in prison at the time. The conference manifesto blamed the cause of the war on imperialism, demanded an immediate end to the war, peace without annexations, and the restoration of Belgium. Clara Zetkin was actually against the conference because she viewed it as sectarian. A point of contention at the conference was the nature of self-determination. Lenin and the Bolsheviks supported self-determination for oppressed nationalities. Rosa Luxemburg, not in attendance, felt that this was a distraction and that national liberation was impossible under imperialism. Lenin argued that national struggle complimented socialist struggle. Another point of contention was whether or not to break with the Second International. Since defenism was still the majority position among socialists, most members of the opposition feared breaking with the international as it would mean being part of a smaller, less viable organization. Rosa Luxemburg disagreed that it was a matter that the organization should decide from within, but should be a worker initiative (Nation, 1989).

The socialist movement continued to debate strategies and the nature of the war throughout the war. As the war continued, anti-war actions increased. For instance, in July 1916, 60,000 soldiers died in a single day at the Battle of Somme. In the first six months of 1916 alone, here were one million war casualties. It is unsurprising that in May 1916, 10,000 people protested in Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. The protest was organized by Rosa Luxemburg’s socialist organization, The Spartacist League. There were also strikes and demonstrations in Leipzig that year (Nation, 1989). In 1916, 200,000 people signed a petition for peace in Britain (Hochschild, 2011). Of course, the most dramatic event was the strike of workers at the Putilov Arms factory on the 3rd of March, 1917. This spiraled into a general strike in Petrograd, the mutiny of the army, and the abdication of the throne after three hundred years of Romanov rule. The February Revolution in Russia resulted in a Provisional Government. In the months that followed, there were mutinies in France and Germany, general strikes and protests across Europe (Nation, 1989). Following the February revolution, 12,000 Londoners rallied in solidarity with the Russians and activists began organizing soviets. In April 1917, there were mutinies in France, wherein soldiers waved red flags, sang the international, and in one case, soldiers hijacked a train and went back to Paris. French troops were diverted from the front to French cities to quell rebellion. At least 30 French army division created soviets. In Russia, the army fell apart as a million soldiers deserted (Hochschild, 2011). The February revolution strengthened the Bolshevik position within the Zimmerwald left, but it took a second revolution, with the Bolsheviks assumption of power to end the war, as the Provisional Government lacked the political will to exit the war (Nation, 1989).

February Revolution in Petrograd

The new Bolshevik government announced an armistice on December 15, 1918 and sent a delegation to meet the Germans at Brest-Litovsk fortress. The delegation consisted of a woman, soldier, sailor, peasant, worker, and at least two Jewish men, all chosen to represent the new society in Russia. The peasant in the delegation, Stashkov, was pulled from the street randomly, but happened to be a leftist. He had never had wine before the meeting and had the unfortunate habit of calling his fellow delegates “barin” or master. The female delegate, Anastasia Bitsenko, made the German delegates, all from the higher echelons of German society, uneasy, as she had just returned from Siberia after a seven year imprisonment for assassinating the Russian Minister of War. Together, these enemies in terms of class, ideology, and war feasted uneasily in honor of the Russian exit from the conflict (Hochschild, 2011). The terms of this exit were settled by a peace treaty in March 1918, which set the conditions of Russia’s exited the World War I at the cost of territorial concessions to Germany. The armistice between the countries antagonized Russia’s allies (Nation, 1989). Russia’s end to the war meant that Germany could devote an addition half million soldiers to the Western Front. It also resulted in more unrest in the warring countries as activists were emboldened by the Russian revolution and immiserated by the ongoing war. Throughout the war, Germany was blockaded by the Allies, which led to food shortages. German troops were reduced to eating turnips and horse meat and civilians ate dogs and cats. Real wages in Germany declined by half during the war. In turn, German submarines downed over 5,000 allied merchant ships, sending 47,000 tons of meat to the bottom of the sea in the first half of 1917 alone. By 1918, war cost made up 70% of Britain’s GDP. 100,000 workers protested in Manchester against food shortages. In July, rail workers in Britain went on strike. Even the police went on strike for two days, as 12,000 London police walked off the job (Hochschild, 2011).

Lenin had pinned his hopes on revolution spreading across the world. Considering the mutinies, desertions, strikes, and protests in 1918, this does not seem entirely far fetched. British military officials even considered making peace with Germany as a way to contain the threat of the Russian spreading revolution elsewhere. March 1918 saw the founding congress of the Communist Party and the Third International, the final break from the Second International. That same year, there were soviets formed in Germany and a sailor mutiny wherein the sailors raised the red flag. 400,000 Berlin workers went on strike in January 1918 demanding peace, a people’s republic, and workers rights (Hochschild, 2011). Revolutions were attempted in Bavaria, Hungary, Braunschweig, and Berlin. Revolutionaries captured the Kaiser’s palace in Berlin and declared a socialist republic. The Berlin Revolution led by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebnecht’s Spartacist League was crushed by Social Democratic Party of Germany in alliance with the German Supreme Command (Nation, 1989). Both revolutionaries were captured, tortured, and executed. The SPD, which had led the member parties of the Second International to side with their belligerent governments, went on to crush other uprisings across Germany, taking its place in the Weimar Republic that followed. Suffice to say, the chasm in the socialist movement that began in 1914 had become an irreparable trench of millions dead and the graves of revolutionaries.

Other Resistance to World War I:

The debates and division within the the socialist movement is certainly an interesting aspect of how war was resisted or failed to be resisted. However, there were many other groups involved in resisting World War One. Another natural source of resistance against World War I might have been anarchists, however, like the socialist movement, the anarchist movement split over how to react to the war. A number of leading anarchists, including Peter Kropotkin, signed the Manifesto of the Sixteen in 1916, which argued that victory over the Central Powers was necessary. The manifesto encouraged anarchists to support the Allies. Kropotkin’s support of the Allies may have been the result of a desire to defend France as a progressive country with a revolutionary tradition. To him, defense of France was a defense of the French Revolution. His approach to the war was pragmatic. He felt that any uprising against the war would be small and easily crushed and that there was a responsibility to defend the country from aggression. He viewed Germany as particularly militaristic. The year that the Manifesto of the Sixteen was written was particularly brutal and saw the beginning of British conscription (Adams and Kinna, 2017).

Not all anarchists were as lost on the issue of war as Kropotkin, for instance, Emma Goldman believed that the state had no right to wage war, drafts were illegimate and coercive, and wars were fought by capitalists at the expense of workers. As the United States moved towards war in 1916, she began using her magazine, Mother Earth, to espouse anti-war ideas. Once the United States entered the war, she launched the No-Conscription League. Subsequently, her magazine was banned and she was arrested on June 15, 1917 along with her comrade, Alexander Berkman (War Resistance, Anti-Militarism, and Deportation, 1917-1919, n.d.). Before she was arrested, Goldman had planned on curtailing anti-conscription speeches, as speakers and attendees of her meetings were harassed by soldiers and police. She was arrested for violating the Selective Service Act, which was passed five days before her arrest. The New York Times covered her arrest and trial, blaming her for two riots that had occurred at her meetings. However, the reports of riots were overblown, as the meetings themselves were peaceful until disrupted by police and soldiers who demanded to see draft registration cards from attendees. Goldman did her best to use the trial as a platform for her ideas, arguing that she didn’t actually tell men not to register for the draft, as according to her anarchist beliefs she supported the right of individuals to make their own choices. She also framed her organizing as part of an American tradition of protest and that democracy should not fear frank debate. Despite her efforts of defending herself and ideas, she was sentenced to the maximum sentence of two years (Kennedy, 1999). Upon serving her sentence at Missouri State Penitentiary, she was deported in December 1919 along with other radicals (War Resistance, Anti-Militarism, and Deportation, 1917-1919, n.d.). Interestingly, Goldman had gained U.S. citizenship when she married Jacob Kershner in 1887, but he had his citizenship revoked in 1909. According to the laws at the time, a wife’s citizenship was contingent on the husband’s. Thus, she was deported based upon the citizenship of her dead husband.

Emma Goldman

European anarcho-syndicalists experienced the same split socialists did, as many came out in support of defensism (Nation, 1989). In the United States, The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was the target of propaganda from the Wilson administration, which claimed that they were agents of the kaiser who were trying to sabotage the U.S. war effort (Richard, 2012). The IWW is an international union with ties to both the socialist and anarchist movements. While not specifically anacho-syndicalist, the IWW was founded several anarcho-syndicalists such as Lucy Parsons and William Trautman. Because the IWW was trying to organize industries important to the war such as mining, lumber, and rubber, they were targeted with Red Scare tactics. To avoid persecution, the leadership of the IWW refrained from taking a public stance against the war, but members were free to critique the war. This tactic did not work and in September 1917, the Department of Justice raided 48 IWW halls and arrested 165 members, some of whom had not been active for years (Richard, 2012). One of the members who was arrested as Loiuse Olivereau, who at the time was an anarchist IWW secretary. After the raid of an IWW office that she worked at, she went to the Department of Justice to have some of her property returned. Among this property were anti-war fliers, which were a violation of the Espionage Act. Like Goldman, she went to trial and tried to make a political defense. She defended herself and her ideas, arguing that wartime repression and zealous nationalism were not “American” values. She appealed to plurality and nationalism based upon internationalism. In her pamphlets, she had emphasized that men who avoided war were not cowards, but brave for living by their convictions. The media gave little attention to her arguments, instead portraying her as a radical foreigner with dangerous ideas, as Goldman had been portrayed (Kennedy, 1999). IWW members who were not arrested faced vigilante justice from lynch mobs. For instance, Frank Little was disfigured and hung from a railroad trestle in Butte, Montana. In 1919, Wesley Everest was turned over to a mob by prison guards in Centralia, Washington. He had his teeth knocked out with a rifle butt, was lynched three times, and shot. The coroner deemed the death a suicide (Richard, 2012).

In addition to anarchists and socialists, suffragists were another group of activists with an interest in anti-war organizing. In addition to the March 1915 socialist women’s conference, there was a much larger women’s gathering at The Hague in the Netherlands. April 1915 conference brought over 1300 delegates together and was organized by suffragists under the leadership of Jane Addams. It was mostly attended by middle class, professionals though representatives from trade unions and the Hungarian Agrarian union was also in attendance. Like the socialist movement, the suffragist movement was divided between those who supported their governments and those who were anti-war. For instance, the International Suffrage Alliance did not support the Hague conference. Invitations to the conference put forth the position that the war should be ended peacefully and that women should be given the right to vote. Attendance was difficult, since it meant crossing war torn countries or asking for travel documents, which was often denied (Blasco and Magallon, 2015). Attending the conference was itself illegal and all 28 delegates from Germany were arrested upon their return. 17 of the 20 British delegates were refused passage by ship when they tried to leave Britain (Hochschild, 2011). Like the socialist conference, the The Hague conference made a resolution that territorial gains or conquests should not be recognized, though it put the onus of ending the war on neutral countries rather than working people. There was no call for a “war on war” but for mediation, justice, and diplomacy through a Society of Nations. Some of the points of this resolution were adopted by Woodrow Wilson in his 14 Points (Blasco and Magallon, 2015).

The sentiment of The Hague Conference, which focused on progressive internationalism, was echoed by the Women’s Peace Party before the war. In 1914, 1,500 women marched against World War I in New York. Fannie Garrison Villard, Crystal Eastman, and Madeleine Z Doty organized the first all-female peace organization, The Women’s Peace Party. After the end of the war, the Women’s Peace Party became the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (Jensen, 2014). Despite the peaceful orientation, the WPP also promised to defend America from foreign enemies and worked to get Woodrow Wilson elected in 1916. They also framed their peace work as a matter of maternal duty as nurturers. Irrespective of their patriotic politics, they were critiqued for being too nurturing or feminine, as this was viewed by men as having a negative and weakening effect on the public sphere (Kennedy, 1999). At the same time, it seems contradictory that a peace party would support national defense. However, supporting the U.S. war effort might be viewed as an extension of the interest of middle class white women in finding increased state power through voting. The war sharpened the differences between radical and reformist suffragists. The New York State Suffragist Party argued that the Silent Sentinels protest outside of the White House was harassing the government during a time of national stress (Women’s Suffrage and WWI, n.d). Even before the United States entered the war, The National American Woman Suffrage Association wrote a letter to Woodrow Wilson pledging the services of two million suffragists. The letter appeared in the New York Times and promised that the suffragists would remain loyal to the war effort by encouraging women to volunteer in industries left vacant by men at war and collect medical supplies and rations (The History Engine, n.d.). The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) engaged in patriotic volunteering, but they did not abandon organizing for the vote. NAWSA’s president, Carrie Chapman Catt was a pacifist, but supported the war effort by promoting Liberty Loans, Red Cross drives, and War Savings Stamps. Around the country, suffragists supported the war effort by planting victory gardens, food conservation, Red Cross and volunteering. The National Women’s Party took a more radical approach, and during the war 200 of them picketed the White House and were arrested, went on hunger strikes, and were forcibly fed. In the United States, women finally won the right to vote in 1920, but this mostly impacted white women as Native American women were not U.S. citizens until 1924 and first generation Asian women were not granted the right to vote until after World War II (Jensen, 2014).

Silent Sentinels who protested outside the White House during WWI

The divide in the suffragist movement is illustrated in the Pankhurst family. Sylvia Pankhurst, was a British suffragist who with her mother Emmaline and sisters, Christabel and Adela, founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) (Miles and McGregor, 1993). Emmaline Pankhurst, the matriarch of the family, became engaged in politics after working with poor women to collect data on illegitimate births. She noted that many of these births were caused by rape and also took issue with the fact that female teachers in Manchester made less than their male counterparts. Thus, sexual assault and the wage gap have a long been observed as social problems by feminists. The WPSU did not allow male members, though they infiltrated meetings of the Liberal Party to demand voting rights. The WSPU eventually split over the issue of whether or not they should support candidates. Emmaline Pankhurst was against this, as all of the candidates at the time were male. Charlotte Despards, a novelist, charitable organizer, Poor Law Board member, and proponent of Indian and Irish independence, was for supporting candidates, as she was a supporter of the Independent Labor Party. Despards went on to found the Women’s Freedom League (Hochschild, 2011). Again, male membership and supporting male candidates are still issues that modern feminist groups consider.

The WSPU was the most radical of the British suffragist groups and it engaged in arson, window breaking, and bomb attacks (Miles and McGregor, 1993). The WSPU burned the orchid house at Kew Gardens, smashed a jewel case at the Tower of London, burned a church, and carved out “No Votes, No Golf” on a golf green (Hochschild, 2011). Due to these activities, suffragists were imprisoned and Sylvia herself was arrested nine times between 1913 and 1914. To protest imprisonment, they went on hunger strikes and had to be forcibly fed. Sylvia was expelled from the WSPU for socialist beliefs and founded the East London Federation of Suffragists. Despite their extreme tactics, Emmaline and Christabel became less radical at the outbreak of World War I and ceased their radical tactics, instead supporting the war and handing out white feathers to shame men to who didn’t enlist to fight (Miles and McGregor, 1993). The eldest sister, Christabel traveled to the United States to drum up support for the war. Most British suffragists supported the war effort, which may seem surprising as many had earlier denounced war, gender essentializing it as a masculine endeavor. This turn towards national defense over voting rights was strategic, as it did offer mainstream legitimacy to suffragists who had otherwise been arrested and persecuted. Even the author Rudyard Kipling had expressed concern that the women’s suffrage movement weakened Britain, making it less prepared for war. The WSPU organized a march of 60,000 women, though not against war. The march was to encourage women to buy shells. Perhaps due to their compliance in the war and part because the Russian revolution had granted universal suffrage, women were granted the right to vote in Britain in 1919 (Hochschild, 2011).

As for Sylvia, one of the few anti-war suffragists, she organized ELFS to set of free clinics to mothers and children, a free day care, a Cost Price restaurant, and a toy factory for fundraising. She supported strikes against conscription, the Defense of the Realm Act, protested the execution of James Connolly, and her group was the only British suffragist organization which continued to organize for the vote during the war (Miles and McGregor, 1993). She had even suggested that an anti-war march of 1,000 women should occur in the no man’s land between enemy lines. Throughout the war, she documented the suffering of women, noting that women were forced out of hospital beds to make room for soldiers or struggle to survive on the military pay of their husbands. The wives of deserters received no pension from the government and women were subjected to curfews to avoid cheating and faced imprisonment if they had a venereal disease and had sex with a soldier (Hochschild, 2011).

Sylvia Pankhurst

In 1916, the organization changed its name to the Workers Suffrage Federation and in 1918 to the Workers Socialist Federation. It was the first British organization to affiliate with the Third International and she herself articulated that while women could win the vote under capitalism, they could achieve liberation. She was arrested for sedition in 1920 for urging British sailors to mutiny over poor conditions and for dock workers to resist loading arms to be used by Russian counterrevolutionaries. While in prison, the Workers Socialist Federation joined the Communist Party. She never joined the Communist Party herself and was critical of the New Economic Program (Miles and McGregor, 1993). Sylvia never joined the party, but paid a visit to the Soviet Union, which impressed her. She continued her activism throughout her life, warning about the rise of fascism and drawing attention to Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia. She eventually moved to Ethiopia, where she died at the age of 74.

Conclusion:

Resistance to World War I in many ways seems like a series of stunning betrayals. The socialists, which had the power to stop the war, sided with their national governments at the cost of millions of lives. The hardships of war created the conditions for unrest in many countries, but it was only in Russia where revolution was successful (at a high cost and with lasting consequences to the shape the new society). Suffragists, like socialists, sided with their national governments. This Faustian deal, in some ways, secured the right to vote. Today, women can vote to send women to kill other women in war, just as socialists voted for the money to arm workers to fight other workers. Anarchists were also fractured by the war, when this group seemed the most ideologically unlikely to side with government war mongering! At the same time, activists of all of these groups made hard choices. Anti-war socialists found themselves unable to organize workers early in the war due to their small numbers and the swell of nationalism and prejudices. Any activist organizing against the war faced imprisonment in beligerant countries, and Emma Goldman, Clara Zetkin, and Rosa Luxemburg among many more were arrested. Some activists faced mob justice and death. Still, there are some lessons to be drawn from all of this. A major lesson is the importance of unwavering internationalism. Another lesson is to take a long, principled view of power. Suffragists abandoned their organizing in the interest of legitimacy and national power. In doing so, they made powerful allies, but they also took their place in the state apparatus that oppresses of women. So too, socialists, who enjoyed popularity and a share of state power, crushed other socialists and supported the violent, senseless slaughter of workers to maintain their place in capitalism. Activists should always stand against imperialism and in solidarity with all of the oppressed people of the world. Doing this may mean standing in the minority or at the margins of history making, but it may also mean keeping alive the idea that a better world is possible and the ideas with the power to build movements that make this happen.

Sources:

Adams, Matthew S., and Ruth Kinna. (2017) Anarchism, 1914-18: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War. Manchester University Press.

AFP. (2018, November 6). France addresses painful history of African WWI troops. Retrieved November 12, 2018, from https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/africa/2018-11-06-france-addresses-painful-history-of-african-wwi-troops/

Blasco, S., & Magallón, C. (2015, April 28). Retrieved October 25, 2018, from http://noglory.org/index.php/articles/445-the-first-international-congress-of-women

Hochschild, A. (2011). To end all wars: A story of loyalty and rebellion, 1914-1918. United Kingdom: Macmillan.

Jankowski, T., 2013. Eastern Europe! – Everything You Need to Know about the History (and More). New Europe Books.

Kennedy, K. (1999). Disloyal mothers and scurrilous citizens: Women and subversion during World War I. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Miles, L., & McGregor, S. (1993, January 01). Suffragette who opposed World War One. Retrieved October 25, 2018, from http://socialistreview.org.uk/395/suffragette-who-opposed-world-war-one

Jensen, K. (2014, October 8). Women’s Mobilization for War (USA). Retrieved November 7, 2018, from https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/womens_mobilization_for_war_usa#Suffrage_Movement

Lenin, V. (2005). Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. Retrieved October 23, 2018, from https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/imp-hsc/

Lenin, V.I. Lenin: War and Revolution, 2005, http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/may/14.htm.

Masebo, O. (2015, July 03). The African soldiers dragged into Europe’s war. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-33329661

Nation, R. (1989). War on War: Lenin, the Zimmerwald Left, and the Origins of Communist Internationalism. Haymarket Books.

Partington, J. S. (2013). Clara Zetkin: National and international contexts. London: Socialist History Society.

Patnaik, P. (2014). Lenin, Imperialism, and the First World War. Social Scientist, 42(7/8), 29-46. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24372919

Richard, J. (2012, November). The Legacy of the IWW. Retrieved November 12, 2018, from https://isreview.org/issue/86/legacy-iww

The History Engine. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2018, from https://historyengine.richmond.edu/episodes/view/5322

Tuchman, Barbara Wertheim. The Guns of August. Ballantine Books, 1990.

War Resistance, Anti-Militarism, and Deportation, 1917-1919. (n.d.). Retrieved November 12, 2018, from http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/goldman/MeetEmmaGoldman/warresistance-antimilitarism-deportation1917-1919.html

Women’s Suffrage and WWI (U.S. National Park Service). (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2018, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/womens-suffrage-wwi.htm