broken walls and narratives

A not so revolutionary blog about feminism, socialism, activism, travel, nature, life, etc.

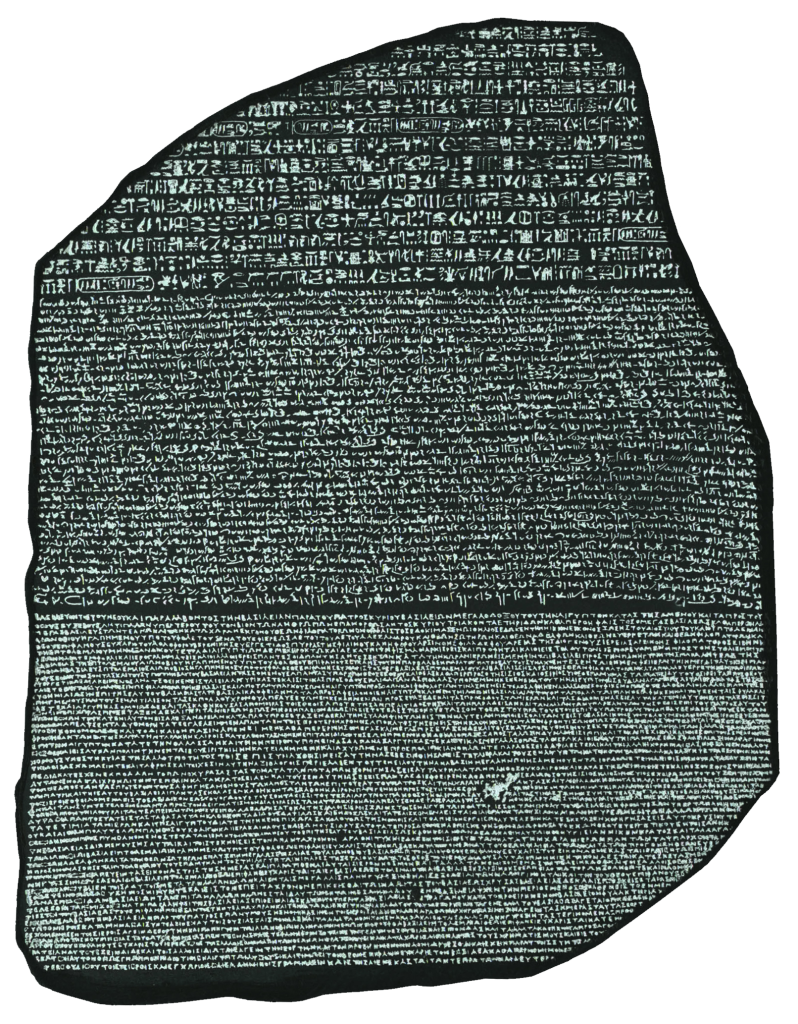

Rosetta Stone

Rosetta Stone

H. Bradford

12/6/22

People on the internet are fighting over the Rosetta Stone.

Everyone on the thread said it belongs in Britain.

Finders keepers

Egyptians would lose it

Muslims can’t be trusted

The French found it first

Those Egyptians aren’t REAL Egyptians.

We owe so much to Western academics.

****

When I wish upon a shooting star,

Sometimes I wish it was a giant rock,

A Rosetta stone that spells cataclysm

To Islamophobes, Imperialists, and ignorance

But asteroids aren’t as precise as drones and missiles.

****

If there were such a stone,

It would certainly be written in English

And in blood

So the language is easy to understand for colonists and apologists.

****

It’s dark to think about.

Maybe this isn’t everyone,

Quiet, kind people don’t post online.

And when has justice ever come from the heavens?

If history is long enough,

Will wrongs be made right?

Because the oppressed are many

*****

And eventually they fight

Feral Brain

Feral Brain

a poem by H. Bradford

Everything feels foreign.

A house full of strange objects.

A body shaped by strange rules.

People are rituals.

That one’s a party,

but where’s the surprise?

Meaning is the meat of domestication,

It softens the teeth

and shortens the jaw.

The world is roads

and prisons

and wars.

But there must be some wilderness left in the frontier of

our genes.

A germ or a seed.

Some small part that wasn’t commodified,

colonized,

or atomized.

There is still some flight and fight

in the feral brain.

For now,

we only howl

at the absurdity of it all.

Survival isn’t Pretty

H. Bradford

08/06/21

Survival isn’t pretty.

There have been dark days before.

Global fires, sunless days, and acid rain.

Those times aren’t for the large, proud, upright creatures.

If you have feathers, fly away.

Hide under that hard, terrapin shell.

Slip into the mud or sea.

Enter a long, slow sleep.

Learn to eat carrion.

Take life from death.

If you have big teeth, now is the time to use them.

If you don’t, grow small, and slip into the shadowy crevices.

Parasites and scavengers have a chance,

But not plants with hungry leaves

and flowers with special needs.

Everything maladaptive is adapted to a time and place.

Time is kinder to snails, sharks, and tardigrades

Than it is to smart, sad monkeys.

Cataclysm settles the score,

A sudden change subtracts what is too precious for the world.

Too precarious in chain of being.

Survival isn’t pretty.

Pretty isn’t made to survive.

The Devastating Effects of Wildfires on Indigenous Communities

7/23/21

H. Bradford

The summer of 2021 has been marked by catastrophic drought, heat, and fires across the United States and Canada. The Bootleg Fire, one of the largest fires in Oregon history, has incinerated an area larger than the city of Los Angeles and forced the evacuation of over 2,000 people. It is one of nearly eighty major fires in thirteen U.S. states. The Bootleg Fire is so large that it generates its own weather and has impacted air quality on the east coast of the United States, 2,500 miles away. The Bootleg fire is the third largest in Oregon history and just one of several large fires in Washington, California and Oregon. The largest Oregon fires were the 2002 Biscuit Fire and the Long Draw Fire in 2012. However, by the time the fire is extinguished, it will likely exceed them in size. These fires are an obvious and apocalyptic result of climate change, as the Western United States has grown hotter and drier over recent decades. As unfettered fossil fuel driven capitalism continues to warm the planet, massive fires are becoming an unsettling norm. These fires impact broad swaths of society, but indigenous people are often on the front line of their most devastating effects.

Although the Bootleg Fire has mostly destroyed rural, forested areas and has spared cities, the blaze is decimating tribal lands. Don Gentry, chairman of the Klamath Tribal Council reported that the fire threatens the tribal lands of the Klamath Tribes. The Klamath Tribes consist of three Native American tribes, including the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahoosin and the fire is just 25 miles from their tribal headquarters. Oregon Public Broadcasting reported that last September, wildfires destroyed at least one home, a cemetery, and land used by the Klamath Tribe for hunting, gathering, and fishing. These fires are the latest in their struggle for survival, as in the face of drought conditions, they have fought to preserve minimum water levels in Upper Klamath Lake. The Guardian reported that farmers also draw water from the lake, which threatens two species of endangered sucker fish that are central to Klamath culture and history. The Klamath Tribes have also sought to demolish dams that imperil salmon runs on the Klamath River. The fires are burning their ancestral homeland. Gentry said that the area has been their home for 14,000 years and is also home to 500 year old growth Ponderosa Pine. The Klamath Tribes historically used controlled fire to periodically destroy the fuel for larger fires. James Johnston, a researcher with Oregon State University’s College of Forestry, reported to NPR that along with climate change fueled heat and drought, poor forest management has contributed to the fires. Fires have not been allowed to burn for 125 years, resulting in a buildup of excess fuel.

In Washington, residents of Nespelem, part of the Colville Reservation, were evacuated due to fires. Residents were able to evacuate before the fire burned seven homes. In response to the Chuweah Creek Fire, The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, a community of 9000 descendants of a dozen tribes, declared a state of emergency and closed the reservation to the public and to industrial activity. The Spokesman-Review reported that it was the third major wildfire on the Colville Reservation in six years. In 2015, 20% of the reservation was destroyed by fire. These fires have destroyed elk, deer, traditional plants, and timber that the tribe relies on for sustenance. The tribe derives 20% of their income from timber, which goes toward per capita payments. Elsewhere, last year’s Slater Fire in California destroyed over 200 homes belonging to the Karuk tribe and disrupted ceremonies and hunting. Many of those who lost their homes did not have insurance, owing to the rising cost of insuring homes in fire prone areas. Aside from houses, the Karuk people also lost important cultural artifacts such as animal hides and century old baskets. The tribe has advocated for more prescribed fires to control future wildfires.

The destruction of forests, bear, elk, deer, cemeteries, homes, and cultural artifacts are just a few of the ways that the wildfires have inflicted loss upon Native Americans of the Western United States. The losses of Native Americans are not prioritized. For instance, FEMA refused to call the wildfire that destroyed the Karuk community at Happy Camp a disaster. This denied the tribe access to additional resources that would have enabled residents to return to their homes. At the same time, when the historical artifacts of the dominant colonizer culture is imperiled, the government goes to great lengths to protect them. When The Mitchell Monument was recently endangered by fire, the monument was saved by the efforts of firefighters to use aerial dropped flame retardant, protective wrap, and fuel reduction. The Mitchell Monument commemorates the death of six Americans killed by a Japanese balloon bomb during WWII. Native American losses barely make the news.

The Western United States is not the only area where fire, heat, and drought are destroying Native American communities. In Manitoba, smoke from wildfires has caused the evacuation of several First Nations communities. According to the CBC, as of July 20th, over 1,600 people were being evacuated, including the entire populations of Little Grand Rapids and Pauingassi First Nations communities. Bloodvein and Berens River First Nations near Lake Winnipeg are also being evacuated to Winnipeg. There were 130 fires burning in Manitoba, of which, over two dozen were considered out of control by officials. Ellen Young, a Bloodvein First Nations Band Counselor, reported to the CBC that the fires were only six kilometers from the community. In a CBC radio interview, Blair Owens, a member of the Little Grand Rapids First Nations argued that not enough resources are being mobilized to fight the fires. In part, this is due to the fact that Manitoba’s forest fire fighting service, including its water bomber fleet, was privatized in 2018.

CBC also reported on July, 21st that there were 167 active wildfires in northwestern Ontario. Of these, 57 were located in the Red Lake District. The Poplar Hill First Nation community, located four miles from the fires, was evacuated. Deer Lake First Nation, located 15 miles from the fire, was also evacuated. On Tuesday July, 20th the provincial government announced the partial evacuation of Cat Lake and North Spirit Lake First Nation communities. 500 people from Deer Lake were flown to Cornwall Ontario. Residents could only bring a single suitcase weighing under 28 lbs and some remained behind to care for pets. The Red Cross has housed evacuees in hotels in Winnipeg, Selkirk, and Thunder Bay, but families must sometimes share rooms with others. Evacuations are a grim reality of wildfires, but impose trauma upon indigenous people who already bear generational trauma from being forcibly removed from their lands and later torn from their families and put into deadly boarding schools.

As Canada burns, construction continues on Line 3. Enbridge, a Canadian company, is racing to complete the 330 mile long Line 3 “replacement” pipeline. Despite fierce opposition from water protectors in Minnesota, the pipeline is nearly 70% completed. On Tuesday, July 20th, activists from a variety of indigenous and environmental organizations gathered at the headwaters of the Mississippi River to speak out against the project, for treaty rights, and to draw attention to water issues. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources had designated 72% of the state in extreme or severe drought. The Mississippi River was low and serves as a source of drinking water to many communities. The driest parts of the state are where the Enbridge Pipeline is currently being constructed, drawing from scarce water resources in the process. Wild rice, a culturally and economically important food to the Anishinaabe people, has been threatened by both the drought and potential leaks from the Line 3 project. On June 4th, the Minnesota DNR issued a permit to Embridge allowing the company to pump up 5 million gallons of water for the remaining 145 miles of pipeline construction. This was nearly 10 times the amount of water that they originally requested. Activists oppose this out of concern that during the drought, dewatering construction sites can put stress on wetlands, lakes, and streams. The DNR considers the state prime for wildfires on account of the drought. There have already been 250 wildfires in the state this summer, when 50 is more typical for June or July.

The recent and increasingly frequent wildfires indicate that even a shred of self-determination of indigenous people is impossible within capitalism. Treaty rights mean nothing if the land that sustains indigenous communities is charred by climate change driven fires. Indigenous struggles against corporate interests for fishing rights, clean water, wild rice beds, land access amount to little of the land itself is too parched by drought. Fire does what capitalism has always done, separate people from land and the means of sustenance outside of wage labor. The fact that Line 3 continues to be built through Native American lands in the face of drought, fire, and pandemic illustrates the cruelty of the profit motive. Climate change threatens the entire planet, but those who are the poorest, most marginalized, and most dependent upon hunting, gathering, and farming will feel its impacts the hardest. This environmental racism is genocide. The lands that are burning are not empty forests, but indigenous lands with the remnants of indigenous communities that have survived 500 years of genocide. More resources must be mobilized to fight these fires and manage forests in ways that are informed by indigenous knowledge and under their control. The privatization of land, fire fighting resources, and water resources and rights must be stopped. For the survival of the planet, fossil fuels and capitalism must be abolished.

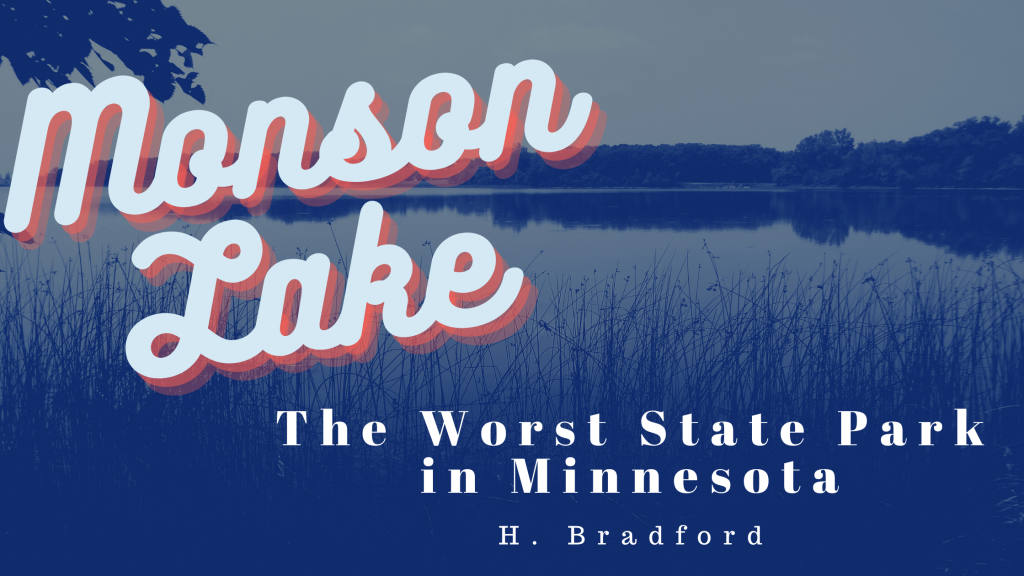

Monson Lake: The Worst State Park in Minnesota

H. Bradford

I am on a slow quest to see every state park in Minnesota. To this end, I visited Sibley State Park with my brother this past weekend. While in the area, we decided to stop by Monson Lake since it was only 17 miles away. There are 75 state parks and recreation areas in the state, so of course, one of them is going to be the worst. Thus far, Monson Lake State Park is the worst on account of its history and size.

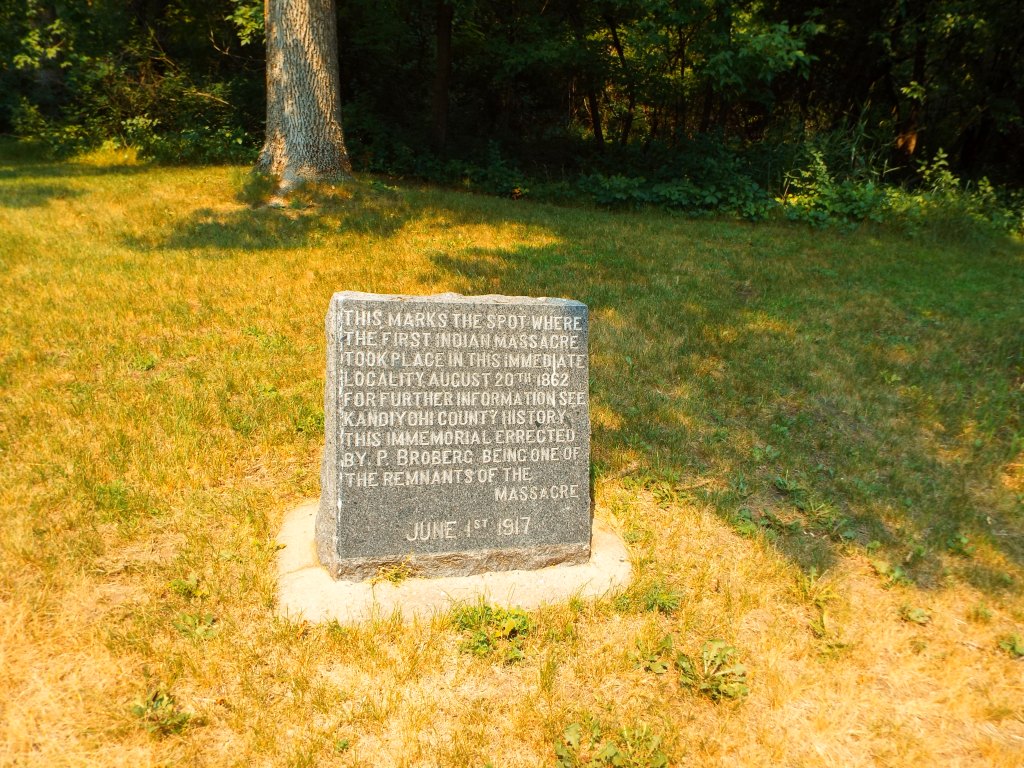

The history of why it was established is the worst aspect of the park. Monson Lake State Park was established in the 1920s as a private memorial park to remember the deaths of 13 Swedish settlers who were killed in the Dakota War of 1862. Since the park is small, this history of the park isn’t masked by size, a large network of trails, or other facilities. There is only one trail, a camp site, the lake, and some signs about the white casualties in the Dakota War. The few signs remain stilted towards colonial history. Although there is brief mention that the conflict arose out of the starvation conditions imposed upon the Dakota people on account of late annuity payments, the signs were more sympathetic to the history of settlers. For instance, the informational sign mentioned that the Dakota people were resisting white civilization, which is loaded language which attributes “civilization” to white people, but not to Native Americans. A more accurate word for what they were resisting was genocide. The sign denotes the names and ages of the colonists who were killed, whereas the impact of the conflict on Dakota people is unspoken and far more horrific. If the park remains, it should expand its signs to include more information about Native American history of the region, more information about the conflict, and also facts about what happened after the Dakota War of 1862. The outcome of the Dakota uprising was the largest mass hanging in U.S. history (when 38 Dakota prisoners were hanged in a single day in Mankato) and mass internment. 1,600 Dakota prisoners of all ages were held near Fort Snelling, of which 300 died that winter. Previous treaties were nullified and the Dakota were forcibly expelled from Minnesota, with a bounty on any found in the state and state sponsored scouting parties to scalp those who remained.

There are several other state parks which have connections to the Dakota War of 1862. Nearby Sibley State Park was named after Henry Hastings Sibley, the first governor of Minnesota and a commander in the Dakota War. The park itself was established by a survivor of the Dakota war who wanted to see a local park established in the area. Fort Ridgely State Park was also established as a memorial to its role in the conflict. This park features a fort defenders monument and the site served as a fort in the war. As mentioned, Fort Snelling State Park was the site of an internment camp after the war. Lake Shetek State Park was established from a site where settlers were buried after the war. Flandrau State Park was named after Charles Flandrau, a settler who defended New Ulm. Since many of these parks are in Southern and Western Minnesota, I have not yet visited them and it may happen that they are worse than Monson Lake. It remains to be seen how and if these parks approach this history. However, the sheer number of state parks with connections to the war should demonstrate that the state park system arose out of a movement to preserve and commemorate a certain version of history. It is easy to treat state parks as benign public spaces to preserve nature, but they are largely white spaces.

Aside from this history, Monson Lake is rather small. It doesn’t seem like a destination in its own right. At 343 acres, it is not the smallest Minnesota State park. However, it featured only one trail, which took less than an hour to explore. The campground and lake seem like they could be locally attractive, but might have been better as a municipal park. The office is not staffed, so visitors must go to nearby Sibley State Park for passes or to speak to a ranger. Again, because of its small size and lack of points of interest, the history seemed like the main attraction.

The park may have some good qualities. For instance, the lake might offer opportunities for birding. My brother and I saw three snakes within the first few minutes of the hike, so the park seems to punch above its weight in reptiles. We also saw chipmunks, toads, a dead turtle, egret, and several other birds. The park is a small area but seemed to have a large number of animals for its size. Again, it probably is a nice local place for a picnic, camping, or fishing, but hardly worth the drive for visitors outside the area. The fact that it is a state park means that it is a protected area, which preserves it from private development. This should be viewed as a plus. But, the history is uncomfortably colonial and this is something which needs to change. Thus, that is why it is the worst state park I have been to.