Jay Cooke, Labor Day, and Crazy Train Capitalism

H. Bradford

Going to Jay Cooke State Park was a Memorial Day and Labor Day tradition in my family. It was one of my grandmother’s favorite spots, as she grew up in the Cloquet area. Growing up, I never considered who Jay Cooke was or what Labor Day meant. Labor Day simply marked the end of summer and the beginning of the school year. It was observed with a picnic and a walk in the park. In researching the history of Labor Day and Jay Cooke, this park is certainly a symbolic place to observe this holiday. Jay Cooke was a capitalist whose bank sent the global economy on a crazy train of capitalistic instability. In part, Labor Day exists because the economy went off the rails in 1873.

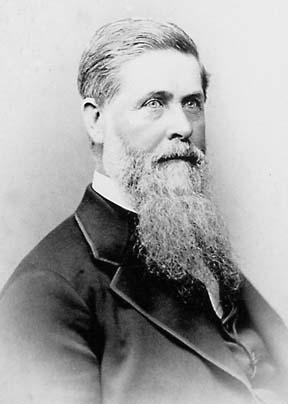

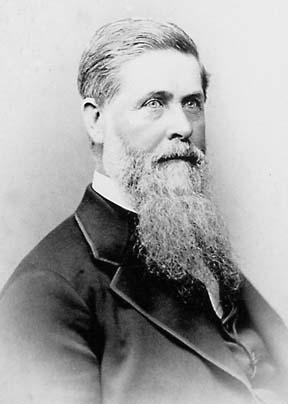

To give a brief overview of Jay Cooke, he was born in Sandusky Ohio in 1821. His father was a railroad investor, real estate speculator, and lawyer (“Jay Cooke, Banker and Railroad Financier,” 2012). It is safe to say that he came from a well-established family, who had lived in the U.S. since 1638 with the arrival of Henry Cooke to Salem, Massachusetts. In addition to his career in investment and law, Jay Cooke’s father, Eleutheros Cooke, was elected to congress in 1830 and President William Harrison stayed at their home. Due to his family’s connections and social position, Jay Cooke enjoyed several well paying jobs before the age of 18 (Lubetkin, 2014). The most significant of these early jobs was in 1839, when Jay Cooke was hired by EW Clark and Company. EW Clark and Company served as a bank and loan broker for railroad companies. He was made a partner in the company after four years, though the company ended in bankruptcy in 1857 during the Panic of 1857 (“Jay Cooke, Banker and Railroad Financier,” 2012). It is notable that Jay Cooke’s first job with a dry goods company also ended in the face of economic downturn during the Panic of 1837 (Lubetkin, 2014). These incidents offer a clue about the nature capitalism during that time period. During the 1800s, there was a transformation of capitalism. Capitalism becomes increasingly financialized, that is, rather than relying on the sale of physical goods in the material world, it entered the realm of investment, debt, and “fictitious capital.” At the same time, capitalism became more international, seeking out new markets and sources for raw materials. Lenin called this dual process of the maturation of capitalism: imperialism. The Panic of 1837 and the Panic of 1857 were only two of the 16 boom-bust cycles between 1854-1919 (Berberoglu, 2012). Economically, the mid to late 1800s were a tumultuous time. This could be understood as part of the growing pains of capitalism, the pains that drove capitalism towards internationalism and the financial sector. These growing pains were not mitigated by modern methods of trying to stabilize capitalism, such as the Federal Reserve (established after the Panic of 1907) or the government spending policies of Keynesian economics.

After the collapse of EW Clark and Company, Jay Cooke set up his own company, Jay Cooke and Company in 1861, on the eve of the Civil War. It is during this time period that he made a name for himself by selling bonds during the Civil War. More than any banker of the time, he became known as the financier of the Civil War for raising $3 billion in bonds supporting of the Union war efforts (“Jay Cooke, Banker and Railroad Financier” 2012). However, he was no stranger to the business of war bonds, as prior to the Civil War, Jay Cooke’s Clark company was one of two companies awarded a $50 million bid to raise money in support of the Mexican-American War of 1846 (Lubetkin, 2014).

To provide some historical context, the Civil War, like all wars, was expensive. At the beginning of the war, the Union’s Treasury only had $1.7 million in reserve for war that cost about $1 million a day. To raise money to fund the war, the North could have raised taxes or printed more money, but neither was sufficient for raising funds. Thus, bonds were used to fund the war. Jay Cooke, on his own volition, spearheaded the effort to raise bond money. He was actually against slavery and initially invested his own money into bonds to demonstrate his belief that bonds were a sound investment. He also targeted farmers, artisans, and merchants for bond sales, rather than only the wealthy. His template for selling war bonds was used again during World War I and II. Because of his success and enthusiasm regarding bond sales, on March 7th, 1862, he was appointed as Subscription Agent for National Loans, which put him in charge of the sales of all US bonds. In 1863, he sold $511 million in bonds, oversaw 2,500 bond sellers, and sold about $3 million in bonds a day. Interestingly, in 1864, the war costed about $3 million a day. In all, Cooke is credited with raising a quarter of the Union’s $6.2 billion in war expenses. Of course, he certainly profited from this venture. His company netted $220,000 or about a 1/25 % of 1% the revenues. At the end of the war, he was worth about $7-10 million dollars and rewarded himself by constructing of one of the nicer mansions of the era, complete with fifty three rooms. It should also be noted, that while he was against slavery, he certainly wasn’t against racism. During the war, Jay Cooke invested in a trolley car service between Capitol Hill and Georgetown. However, he did not allow African Americans to ride the trolleys, even if they were serving in Union regiments. When confronted about the policy, he avoided the issue by selling the company. Another example of his less than moral behavior was that he also sold bonds to Quackers, telling them that the bonds would build hospitals, when in fact they money was not specifically earmarked (Lubetkin, 2014).

After the war, Jay Cooke turned his attention to railroad investment though he was a latecomer to this investment arena as there was already a transcontinental railroad when he agreed to help finance the Northern Pacific Railroad (“Bubbles, Panics, and Crashes” 2012 ). Between 1865 and 1866, Cooke began purchasing large tracts of land in Minnesota and visited Superior and Duluth. In 1868, he sold $4.5 million dollars in bonds to fund the Lake Superior and Mississippi Railroad. (Lubetkin, 2014) Later, Gregory Smith, the president of the Northern Pacific Railroad Company approached Jay Cooke and Co. for a $5 million loan. Construction began at NP Junction in Carlton (“Brainerd Owes its Existence,” 1971). His investment in that railroad is why we are here today in Jay Cooke State Park. The Munger Trail was once a section of Northern Pacific Railroad that connected Duluth to Minneapolis. To put his investment into a larger economic context, 1865-1873 was a booming time for the US economy (Barga, 2013). Arguably, despite some downturns, this was part of a larger unprecedented economic boom between 1848 to 1873. Once again, capitalism was becoming more international. World trade actually increased 250% between 1850 and 1870. This is even more astonishing when one considers that world trade had already increased 100% between 1800 and 1840 (Faulkner, 2012). Owing to the industrialization of the U.S., Britain, and Western Europe, one area of rapid growth was railroads. Between 1865 and 1875, $7.25 million dollars was invested in railroads in the United States. During this time period, 30,000 miles of new track was laid, doubling the miles of railroad in the country (Barga, 2013). Of course, like funding the Civil War, constructing these railroads was tremendously expensive. Prior to the Civil War, roads had been funded by local investors. However, due to the scope of creating a transcontinental railroad system, the Federal Government once again sought bonds from banking houses to fund the railroads. Thus, many of the bankers who had negotiated Civil War bonds, became involved in financing railroads (White, 2003).

To fund the massive expansion of railroads, the railroad companies went into bonded debt. Railroad debt accounted for $416 million in 1867, $2.23 billion in 1874, and $5.05 billion in 1890 (White, 2003). The hope was that the construction of railroads would eventually lead to profits through shipment of goods, extraction of new resources, and construction of new communities. In this region in particular, it would enable the transport of goods to be shipped over the Great Lakes. However, construction was costly, as railroads has to be built through swamps, mountains, and Native American land. In short, it was a risky investment. Despite this, there was a “railroad mania” as investors purchased railroad bonds and securities. This frenzy to invest spread into Europe, as about ⅓ of railroad securities and bonds were from England. The profits from new railroads did not match the expansion (Barga, 2013). There was also significant investment from included significant from Great Britain, Germany, and the Netherlands (White, 2003). As an interesting side note, Germany’s investment in railroads was fueled by indemnity payments from the Franco-Prussian War, a war which preceded the Paris Commune (“Bubbles, Panics, and Crashes” 2012). Despite the risky investment, financiers and railroad companies carefully crafted a rosy narrative of profitability. Jay Cooke’s banking banking house emerged from the Civil War with a trustworthy, moral, and a patriotic veneer, lending legitimacy to the bonds. However, even this had limits, as in 1872, Cooke advised his brother to try to control the Associated Press from releasing unfavorable information about the Northern Pacific Railroad, as not to scare off investors. As the railroad expenditures outgrew the investment, Jay Cooke advanced his bank’s money into the Northern Pacific. But, this rendered bankers unable to withdraw funds from his banking house (White, 2003).

The railroad bubble burst in September of 1873. Fear of overcapacity, high costs, and the Credit Mobilier scandal (wherein politicians were bribed with discounted railroad stock), made investors lose faith in railroads and depress the bond prices. As a result, Jay Cooke’s bank closed its doors in September. This resulted in a panic, run on banks, the stock market collapse, and a worldwide depression that lasted into the 1890s. This economic downturn is known as the Long Depression (White, 2003). Jay Cooke’s bank collapse resulted in the collapse of 98 banks, 89 railroad companies, 18,000 other businesses (Faulkner, 2012). By 1875, 65% of the American railroad bonds held by European investors had defaulted (White, 2003). Nevertheless, The Long Depression was by no means as intense as the Great Depression. In the US, the economic growth rate only declined from 6.2% to 4.7%. Jay Cooke himself died a wealthy man due to his investments in Utah silver mines (“Jay Cooke, Banker and Railroad Financier”) and the fact that he may have hidden two million dollars (Bellesiles, 2010). Nevertheless, he did have to sell his mansion and moved in with his daughter, where he lived until his death 31 years later (Bellesiles, 2010). It is hard to sympathize with Jay Cooke’s plight as the impact of the Long Depression was far worse for millions of workers. To quote an account from the the Brainerd Dispatch (1971):

“I was employed in the capacity of yard clerk in the lumber yard under the late J. C. Barber. One day in September, 1873, he brought me a copy of a telegram announcing the failure of Jay Cooke. The significance did not impress me until a few days later, when I was discharged, along with two-thirds of the entire shop force. Then came several years of the hardest times Brainerd has ever seen; the population dwindled to less than half of what it was in 1872…..”

This worker’s experience was not unique, as one in seven Americans was out of work in 1876 (Faulkner, 2012). Railroad construction halted, as railroads could not fund their projects or pay their workers. Railroad workers were the first to be hit by the crisis and many became homeless as their housing was connected to their job. Union membership declined during the Long Depression as there were fewer workers to join unions. Prices rose on everyday goods, adding to the struggles of everyday life. Previous gains of the labor movement were reversed. During this time period, unemployment and child labor increased (Barga, 2013).

In Marxist terms, this kind of event in capitalism results from the crisis of overproduction.

“In these crises, there breaks out an epidemic that, in all earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity — the epidemic of over-production. Society suddenly finds itself put back into a state of momentary barbarism; it appears as if a famine, a universal war of devastation, had cut off the supply of every means of subsistence; industry and commerce seem to be destroyed; and why? Because there is too much civilisation, too much means of subsistence, too much industry, too much commerce. (Marx, 1848)”

In other words, there arises times in capitalism where there is too much production. The main reason why this results in a crisis is that profits decline over time as new technologies are capable of reducing production costs. For instance, the first railroad in England, which connected Liverpool and Manchester, allowed rail travel at speeds little faster than a bicycle. But, the railway was highly profitable, offering 9.5% annual dividends, a profitability that would never again be matched by a British railroad (Wolmar, 2007). Technology quickly improved, resulting in faster trains and more capacity to move goods. Technological innovation increases production, but also diminishes profits as more money must be invested in new technologies. Because profits come from wages, there is pressure to decrease wages as profits decline. This strategy has a long term impact of reducing the spending power of laborers. Thus, this results in less consumption of goods, or a problem of too much production compared to consumption. This kind of crisis results in the collapse of companies. With fewer companies, there is more competition, which also results in less profit margin. To increase profits, capitalists increase exploitation. This is exactly what happened in the Long Depression as the few remaining railroad workers experienced a deterioration in wages and conditions. In the bigger picture, as a result of the Long Depression, capitalism changed, becoming more closely connected to the state and more monopolistic. During this period, countries also became more protectionist. For instance, the U.S. had tariff rates of 30%. Countries also became more colonial and invested more in arms expenditures. Arguably, this increase in military spending set the stage for WWI (Faulkner, 2012). Another outcome of the Long Depression was that it enabled the U.S. to emerge as a greater economic power as Britain faltered (Sassoon, 2013).

Besides having an impact on global capitalism, the Long Depression had an impact on the labor movement. For example, in 1877 wages were cut across various railroad companies. In May of that year, the Pennsylvania Railroad Company cut wages 10%. Wages were cut an additional 10% that June. Pennsylvania Railroad Company also decided to double the length of eastbound trains without increasing the number of crew. At the same time, The Baltimore and Ohio line reduced the workweek from three to two days and cut the wages of workers making over a dollar by 10%. Each of these are examples of capitalists trying to extract more relative surplus value from the labor of the workers. Relative surplus value is the profit gained from reducing wages or increasing the productivity of workers. Because of these cuts, the workers went on strike. The Great Railroad Strike was the first general strike in US history and first major railroad strike. 100,000 workers participated by walking off their jobs, destroying property, and halted business (Barga, 2013). To break the strike, 60,000 militia members were mobilized throughout various states. In Pittsburg, the local militia actually sided with the strikers so the National Guard was called upon to quell the strike. Troops fired on a crowd, killing three children and in all, 100 people died in the strike.

The Long Depression also accounts for why, in the 1880s, George Pullman decided to reduce wages and lay off workers for the Pullman Palace Car Company. Demand for railroad cars had simply evaporated (Delaney, 2014). Beyond the reduced wages and layoffs, workers of the The Pullman Palace Car Company, a company which made sleeping cars, were required to live in Pullman City. Clergy in the city had to pay rent to use the church and workers had to pay to use the library. Wages fell 25% during the depression, but rents did not decrease. Furthermore, workers who accumulated debt had it taken out from their paycheck. Because of these conditions, 3,000 Pullman workers went on wildcat strike in May 11, 1894. The strike was made national when, Eugene Debs, the founder of the American Railroad Union, spearheaded a boycott any Pullman cars, with the exception of mail cars. In all, 50,000 railroad workers walked off of their jobs and there was no movement of rails west of Chicago (Brendel, 1994). In July 1894, President Grover Cleveland sent 12,000 federal troops to crush the strike (Delaney, 2014). During the confrontation in Chicago, the U.S. Army and Marshalls killed 30 striking workers (Warren, 2014). The strike was declared over on August 3rd 1894. In the end, Eugene Debs went to prison, the American Railroad Union was disbanded, and Pullman employees were made to pledge not to unionize again (Delaney, 2014). Once the strike was ended, Cleveland signed legislation in support of the creation of Labor Day (Warren, 2014), but he did not win re-election that year (Warren, 2014).

While the Pullman Strike played a pivotal role in Cleveland’s support of Labor Day, the holiday had been in the works for many years. During the French Revolution, a special day was set aside in September to honor labor. The first Labor Day was celebrated in Australia in 1956 and there were early Labor Days in Boston in 1878 and Toronto in 1872 (Ruyle, 2014). During the 1880s as the economy began to recover from the initial shocks of the Long Depression, workers began once again to join unions and agitate. In 1882, the Central Labour Union was formed in New York. The CLU proposed a “monster labor festival” and developed plans for a parade and picnic on Sept 5th, 1882 (Freedman). This idea was actually proposed by Maguire and Mcguire, two members of the Socialist Labor Party in New York (Ruyle, 2014). 10,000 men and women participated in a parade that was it was watched by over a quarter million people. The marchers in the parade carried placards with slogans such as “Less Work, More Pay,” “Labor Built this Republic, Labor Shall Rule It” and “To the Workers Should Belong All Wealth.” Two years later, the AFL called all workers to celebrate Labor Day on the first monday in September. In 1886, 35,000 people participated in a Labor Day march in Chicago. In 1887 Oregon made it a state holiday. And, of course, after the Pullman strike, Grover Cleveland made it a federal holiday in 1894 as a consolation workers. However, by this time, the radical slogans of the original Labor Day celebrations had become more subdued. Because of increased state repression in the wake of Haymarket massacre in 1886, the AFL distanced itself from red flags, radical speakers, and internationalism at Labor Day. Labor Day was promoted as less radical alternative to May Day, which granted it state sponsorship (Freedman, n.d.). Because of this state sponsorship, Labor Day has generally been seen as more respectable and American. It has even been denounced as a capitalist handout by the Socialist Labor Party, despite the fact that they were part of the founding of the holiday! (Ruyle, 2014). During the 1930s it became centered on organized labor again, though over the years with the decline of the labor movement, its celebration has waned (Freedman, n.d.).

This leads me back to the beginning. At one time, I was a little girl having a picnic with my family at Jay Cooke State Park. I didn’t even know who Jay Cooke was or what Labor Day meant. This is probably representative of how most people in the U.S. spend Labor Day. It is a holiday to celebrate the end of summer. The holiday is divorced from its history. This is because many of us are divorced from the labor movement. That is, most of us are not union members or know about labor history. Most of us don’t even consider ourselves working class. We are part of the mushy, meaningless, amorphous “middle class,” a term that obscures our place in the economy. We are surrounded by all kinds of histories and connections, but live in an isolated moment and in alienated relationships. If we saw the history and connections, we might see ourselves and this moment as part of something bigger and something potentially more powerful than capitalism. In this moment, I am writing a presentation which I will give at Jay Cooke State Park on Labor Day. Jay Cooke was capitalist who played a major role in unleashing the Long Depression on the global economy. The economic downturn impacted workers, especially railroad workers, who went on some major strikes during this period. Labor Day came out of this era of struggle. While it is often viewed as the less radical sibling of May Day, both holidays came out of the struggle of workers for better lives and a better world. As such, Labor Day does not have to be consigned to family picnics in the park. It can be reclaimed and revitalized. Once I was a child, innocent and ignorant. I grew into a radical and continue to grow as I engage in social movements. With the help of social movements, places and holidays can grow and change too.

Sources:

Barga, M. (2013). The Long Depression (1873-1878). Retrieved September 03, 2016, from http://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/eras/civil-war-reconstruction/the-long-depression/

Bellesiles, M. (2010). 1877: America’s year of living violently. New Press, The.

Berberoglu, B. (Ed.). (2012). Beyond the global capitalist crisis: The world economy in transition. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd..

Brainerd owes its existence to Northern Pacific Railroad. (1971). Retrieved September 4, 2016, from Brainerd History, http://sections.brainerddispatch.com/history/stories/rai_1002030058.shtml

Brendel M. (1994, December). The Pullman Strike. Retrieved September 03, 2016, from

http://www.lib.niu.edu/1994/ihy941208.html

Bubbles, panics & crashes – historical collections – Harvard business school. (2012). Retrieved September 4, 2016, from http://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/crises/1873.html

Delaney, A. (2014, September 01). The Bloody Origin of Labor Day, Retrieved September 03, 2016, from

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/09/01/labor-day-2014_n_5738262.html

Faulkner, N. (2012, February 06). A Marxist History of the World part 61: The Long Depression, 1873-1896. Retrieved September 03, 2016, from http://www.counterfire.org/a-marxist-history-of-the-world/15498-a-marxist-history-of-the-world-part-61-the-long-depression-1873-1896

Freeman, J. (n.d.) Labor Day: From Protests to Picnics, Retrieved September 03, 2016 from

http://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/populism-and-agrarian-discontentgovernment-and-civics/essays/labor-day-from-protest-p

Jay Cooke, Banker and Railroad Financier. Retrieved September 03, 2016 from American Rails http://www.american-rails.com/cooke.html

Lubetkin, M. J. (2014). Jay Cooke’s Gamble: The Northern Pacific Railroad, the Sioux, and the Panic of 1873. University of Oklahoma Press.

Ruyle, E. (2014, August 31). The True History of Labor Day: Debunking the Myth, Retrieved September 03, 2016 from https://www.popularresistance.org/the-true-story-of-labor-day-debunking-the-myth/

Sassoon, D. (2013, April 29). To Understand this Crisis we Can Look to the Long Depression Too. Retrieved September 03, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/apr/29/long-depression-crashes-capitalism-history

Warren J. (2014, August 31). Retrieved September 03, 2016 from

http://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/history-labor-day-forgotten-article-1.1923299

White, R. (2003). Information, Markets, and Corruption: Transcontinental Railroads in the Gilded Age. The Journal of American History, 90(1), 19-43. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.akin.css.edu/stable/3659790

Wolmar, C. (2007). Fire & Steam: a new history of the railways in Britain. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-84354-630-6.

Posted in

holiday,

outdoors,

Politics/Ideas,

socialism,

Uncategorized and tagged

1873,

1877,

Civil War,

Crisis of Overproduction,

Great Railroad Strike,

Jay Cooke,

Labor Day,

Long Depression,

Pullman Strike,

railroad,

socialism |