Celebrating Minnesota Chickadees

Celebrating Minnesota Chickadees

H. Bradford

2/23/19

There are many Minnesota birds that I have never seen. Until early February, a Boreal chickadee was one of them. In previous winters, I made some efforts to find a Boreal chickadee at the Sax Zim bog. I would check e-bird and scope out the place where they were often seen (Admiral Road Feeder). No matter how long I waited, I never seemed to catch one. I listened to my bird call CD, trying to memorize their more nasal song so that if one was in the area, I would know. Finally, this year, at least according to e-bird, Boreal chickadees were recorded in larger numbers than the last two winters. So, in honor of FINALLY seeing a few of them, here are some chickadee facts to inspire others to celebrate and cherish Minnesota chickadees!

Chickadees are part of the Paridae family, which contains 55 species of birds that are found primarily in Eurasia, Africa, and North America and include birds such as titmice, tits, and chickadees (Otter, 2007). In Minnesota, there are three species of Paridae, which include Black-capped chickadees, Boreal chickadees, and Tufted titmice. Boreal chickadees and Black-capped chickadees are both members of the genus Poecille, whereas Tufted titmice are in the genus Baeolophus (Explore the habits of the breeding birds of Minnesota. n.d.). The members of the Paridae family arrived in North America from Asia 4 million years ago. The tufted titmouse traces its lineage to this earliest wave. A second wave of Paridae arrived in North America 3.5 million years ago and led to chickadees (Otter, 2007). Speciation was the result of isolation from glaciers and expanding desert grassland (Gelbart, 2016). Tufted titmice are found in southeastern Minnesota. Black capped chickadees are the most common Parid in Minnesota, ranging throughout the state with larger concentrations around Lake Superior. Finally, Boreal chickadees are uncommon in Minnesota according to the Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas and can be found in the arrowhead region of Minnesota as well as the far north of the state. There are estimated to be 1.1 million breeding adult Black-capped chickadees in Minnesota, but the number of Boreal chickadees is unknown for lack of observations. Tufted titmice are also uncommon, with a breeding population of under 100 birds. However, due to climate change, winter bird feeding, and the maturation of deciduous forests, Tufted titmice populations in the state are increasing at an average of 1.08% per year. (Explore the habits of the breeding birds of Minnesota. n.d.). Because Tufted titmice are not found in my region and because they are not “chickadees” or part of the genus Poecille, they will not be given further attention in this piece.

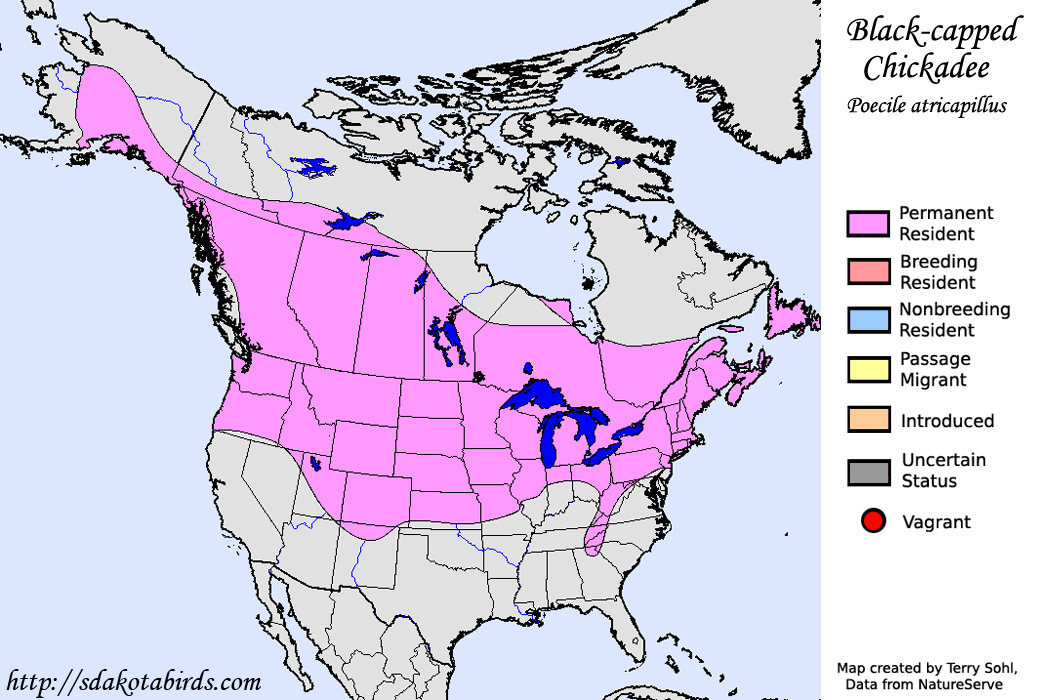

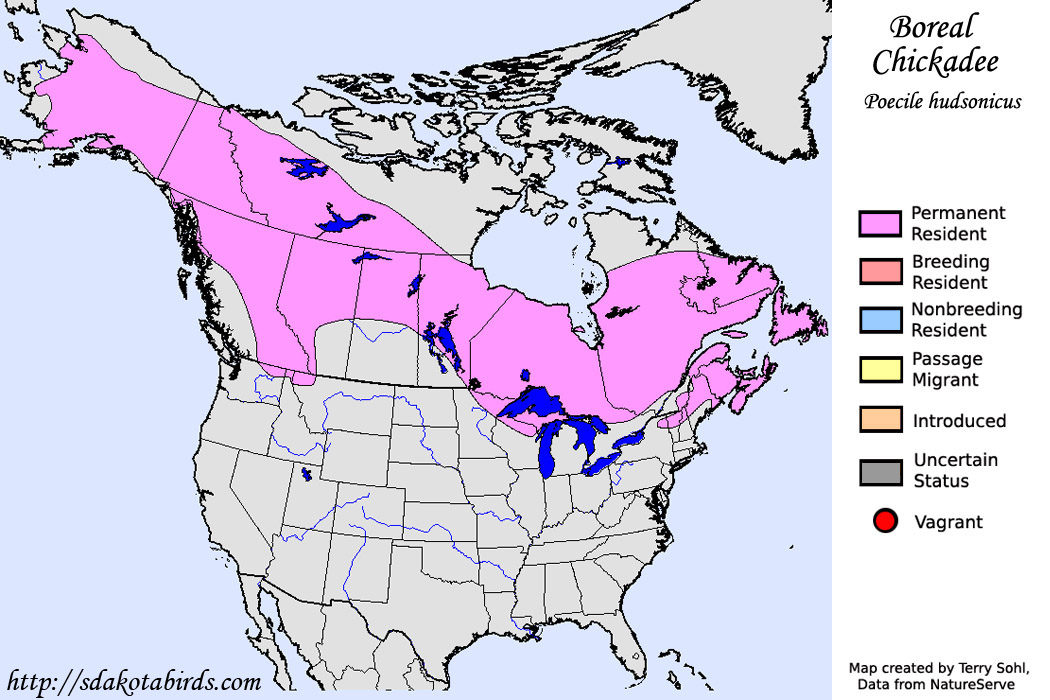

Two maps to compare the ranges of Black capped and Boreal chickadees

Black capped chickadees are extremely common in the winter months in Minnesota. They are iconic, as their image is often used on holiday cards and ornaments. Of the seven species of chickadees in North America, the Black capped has the largest range, spanning all the way from Alaska to California and from the Pacific and Atlantic coasts (Smith, 1997). The bird is easily identified by its black cap and bib, white cheeks, and gray back. To me, these active, curious, even aggressive little birds remind me of tiny Orca Whales or oreo cookies. Orcas and oreos aside, Black capped chickadees look very similar to the Carolina chickadee, which is found in the south eastern half of the United States. The two can hybridize and learn each other’s songs, which can make identification harder where the ranges overlap (Galbart, 2016). So, birds in Kansas, Illinois, Missouri, or Ohio for example might be harder to distinguish, though Carolina chickadees have less white on their wing coverts and have a sharper division between their bib and pale underparts (Smith, 1997). Northern Minnesota is far from the range of Carolina chickadees, so this is not something that I typically have had to worry about. Black capped chickadees bear a resemblance to Boreal chickadees as well, but Boreal chickadees have a brown cap, smaller white cheeks, brown and gray back, and rusty brown flanks (Boreal Chickadee Similar Species Comparison, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Despite their similar appearance and northerly ranges, research suggests that Black capped chickadees are more closely related to Carolina chickadees and Mountain chickadees than they are to Boreal chickadees. Boreal chickadees are more closely related to Mexican chickadees and Chestnut backed chickadees. These species may have existed for two million years (Gill, Mostrom, Mack, 1993).

There are a few characteristics that make Black capped chickadees interesting birds. The first is that they are known for their memory (this is true of chickadees in general). In studies of Black capped chickadees, it has been found that they are capable of finding their food caches using memory. Their ability to remember is based upon overall location, position in relationship to other objects, and finally, color. Chickadees can store hundreds of food items a day and all North American chickadees and tits are food storers. Black capped chickadees can remember where they stored items for at least four weeks (Otter, 2007). In an experiment conducted in a large indoor aviary which tested of what, when, where memory, Black capped chickadees were found to have all three types of memory. The chickadees could remember what (if a stored item was sunflower seeds or meal worms), where (where these items were stores), and when (if the mealworms should be avoided because the passage of time would have degraded the flavor). However, a similar experiment conducted in a less natural cage did not demonstrate a memory for how long meal worms were palatable, which means more studies should be conducted. Chickadees are the only food storing birds outside of corvids (crows, jays, ravens) that have demonstrated what, where, when memory (Feeney, Roberts, Sherry, 2009).

Another interesting characteristic of Black capped chickadees is their vocalizations. For instance, during the winter, spring, and earlier summer, male chickadees studied in Wisconsin were found to make two note Fee-Bee calls while alone and moving through their territories. A faint Fee Bee vocalization was used by both male and female Black capped chickadees to communicate while the female is incubating eggs. Black capped chickadees make a gargling vocalization to warn others before they attack. Probably the most recognizable is the chick-a-dee call, which is used as a warning and to coordinate movements. There are also broken dee and begging dee vocalizations. Black capped chickadees also twitter, hiss, tseet, and snarl. Researchers have identified at least eleven different chickadee calls (Ficken, Ficken, and Witken, 1978). Chickadees are social birds, forming flocks of six to eight birds in non-breeding seasons. To communicate with each other, they have developed elaborate vocalizations. For instance, they have two alarm calls: the chickadee call and the seet. The chick-a-dee call is a mobbing vocalization, which recruits other chickadees to harass a predator. But, it also communicates information about food and types of predators. The alarm for smaller predators vocalized with more “dees” at the end. When the small predator alarm call was played back, Black capped chickadees exhibited more mobbing behavior. Smaller predators may be a bigger threat to chickadees because they are more maneuverable. Predators on the move are vocalized by a seet call whereas those that are stationary are met with the chickadee call (Templeton, Greene, and Davis, 2005). In sum, quite a bit of information is conveyed in chickadee vocalizations.

A final interesting quality about Black capped chickadees is that they are great survivors. Black capped chickadees survive in regions with harsh winters through adaptations such as caching food, cavity roosting, and entering a state of controlled hypothermia at night. By reducing their body temperature at night, Black capped chickadees may reduce their energy expenditure by 32%. To survive during the day while foraging in cold temperatures, Black capped chickadees have the ability to increase their metabolism to stay warm. Their ability to increase their metabolism exceeds other passerine birds that have been studied and approaches some mammals (Cooper and Swanson, 1994). Black capped chickadees are also survivors inasmuch as they are generalists that make use of a variety of environments. They prefer mixed deciduous and conifer forests and as cavity nesters, depend upon decaying trees or snags, but can survive in disturbed environments (Adams, Lazerte, Otter, and Burg, 2016). In Minnesota, Black capped chickadees are most commonly found in pine forests, followed by developed areas, upland conifer forests, pine-oak barrens, and oak forests. Cropland, marshes, and upland grasslands are the habitats wherein Black capped chickadees are the least common, owing the lack of trees (Explore the habits of the breeding birds of Minnesota. n.d.). Black capped chickadees have a diverse diet of berries, seeds, and insects throughout the year, except the breeding season wherein they are insectivores. Although Black capped chickadees are generally widespread, they are impacted by habitat disruption that limits tree cover. This limits genetic variation as populations are fragmented and indicates that climate change could negatively impact the species as tree species shift and narrow in distribution (Adam, Lazerte, Otter, and Burg, 2016). In other words, Black capped chickadees could become less common or at least less genetically diverse with the northern expansion of grasslands due to climate change.

Moving on to Boreal chickadees, because they are less common and located in less populated areas, they have not been researched as thoroughly as Black capped chickadees. But one immediately clear characteristic of these birds is that they are not the generalists that Black capped chickadees are. Boreal chickadees, as the name suggests, are a boreal species. Boreal forests are primarily found between 50 and 60 degrees N latitude, have long cold winters and short cool summers, and are sandwiched between tundra to the north and temperate deciduous forest to the south. Boreal forest climate is wet in the summer and dry in the winter and the forest itself consists of conifer trees and poor soils. The southern part of Boreal forests tend to consist of spruce and hemlock, while pine and tamarack dominate the forests further north where fewer trees can be supported due to nutrient poor soils (Nelson, 2013). The North American boreal forest is largest of the five major forests of the world that are considered largely intact. The others are the Amazon, Russian Boreal forest, Congo basin, and forests of New Guinea and Borneo. The North American boreal forest is 1.2 billion acres and an important nesting ground to billions of breeding birds. Boreal forests are also important in moderating the Earth’s climate, as they sequester 208 billion tons of carbon. Boreal chickadees are permanent residents of Boreal forests and prefer a habitat of balsam fir and spruce. The northern limit of their range coincides with the northern limit of white spruce trees. The southern range limit is the northern United States, where boreal forests meet deciduous forests. As a whole, it is estimated that 88% of Boreal chickadees breed in boreal forests. Like Black capped chickadees, they eat insects, berries, and seeds and they also cache their food as a winter survival tactic. Because of its northerly range and preference for the interior of spruce forests, it is observed less often than Black capped chickadees (Boreal Chickadee “Poecile hudsonica”, 2015).

A study of Boreal chickadees at Forêt Montmorency in Quebec, Canada, found that the birds had a mean flock size of four individuals and a range of three to eight individuals, which is smaller than Black capped chickadee flock size, which often consisted of six to eight individuals. Sixteen of 85 flocks contained at least one Black capped chickadee and 24 flocks contained at least one red-breasted nuthatch. The red-breasted nuthatches were more loosely associated as they foraged together, whereas the Black capped chickadees remained in close contact with the Boreal flock (Hadley and Desrochers, 2008). In areas of Michigan where both Boreal and Black capped chickadees were found, Boreal chickadees foraged in three conifer species, with 76% being black spruce. Black capped chickadees foraged in six conifer and three deciduous tree species. Both species often forage together in mixed flocks. Boreal chickadees generally prefer dense conifer forest and Black capped prefer open mixed forests. Boreal chickadees were found to spend more time foraging higher on the trees. Both spent similar amounts of time in middle zones of the tree and little time at the bottoms of trees. Trees used by Boreal chickadees were tamarack, Black spruce, and white spruce, which minimized competition with black capped chickadees. Both forage for pupae, dormant caterpillars, and insect eggs, but their strategies helped to avoid competition (Gayk and Lindsay, 2012). Minnesota is unique in that it is one of just a few states in the United States where the ranges of the two birds overlap.

Although Boreal chickadees are less vocal than Black capped chickadees (Otter, 2007), they do have many vocalizations with which they communicate. Like Black capped chickadees, they produce a “chickadee” call, which has many variations and is used for such things as communication between males and females during nest excavation and to scold other birds or predators ((McLaren, 1976). ). Compared to the Black capped chickadee, the Boreal chickadee’s “chickadee” call is often described as more nasal. Boreal chickadees also make a “seep” call which is similar to the contact call between Black capped chickadees. A sharp seep call is used to warn against predators. Boreal chickadees also hiss, trill, and make begging sounds. Like Black capped chickadees, they make a chit sound, which Black capped chickadees use to warn of ground predators and Boreal chickadees use for unknown purposes (McLaren, 1976). Unlike Black capped chickadees, Boreal chickadees do not produce a whistled song (Boreal Chickadee “Poecile hudsonica”, 2015). In a study of Black capped chickadees at Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario, a total of eighteen calls were observed (McLaren, 1976).

Because Boreal chickadees are only adapted to boreal forests, climate change is likely to have dire consequences for the species. Models predict that moose, caribou, spruce grouse, and Boreal chickadees will have entirely separate east and west populations as habitat is fragmented and pole-ward shifts in ranges. The east west divide may occur due to a vulnerable swath of boreal forest on the border between Quebec and Ontario. The slim section of forest is the narrowest swatch of boreal forest in North America and a place where boreal meets deciduous forest. By 2080, Boreal chickadees could be extirpated from this region (Murray, Peers, Majchrzak, Wehtje, Ferreira, Pickles, and Thornton, 2017). Minnesota is particularly vulnerable to climate change because the state is at the crossroads of three biomes: conifer forest, decidious forest, and prairie. At the same time, the temperature of Minnesota has gone up 3-5 degrees since the start of the last century. Duluth could have a climate more similar to Minneapolis in 50 years and the state as a whole could eventually become more like Nebraska, with the expansion of grasslands and oak savanna. Boreal forests will disappear from the state, and with them, perhaps 36 species of birds, including Boreal chickadees (Weflen, 2013).

Minnesota has two great species of chickadees (not including the tufted titmouse), but both could shift northward out of the state with climate change. Boreal chickadees are particularly vulnerable, as they are less common and an obligate boreal species. The loss of boreal forests is further troubling because the role these forests play in sequestering carbon. Black capped chickadees require trees to survive the winter and roost at night, so the expansion of grasslands or loss of trees does not bode well for the otherwise plentiful and adaptable bird. Although chickadees are sometimes taken for granted as common bird feeder birds, it turns out that they are intelligent and well adjusted to the harsh winters of Minnesota. Their vocalizations are complex and convey a plethora of important information about everything from predators to territory. Chickadees have made their home in the Americas for millions of years, so it would be tragic to undue millions of years of evolutionary history through the wanton warming of our climate through human activity and dependency on fossil fuels. The best way to celebrate Minnesota chickadees is to mobilize against climate change!

Sources:

Adams, R. V., Lazerte, S. E., Otter, K. A., & Burg, T. M. (2016). Influence of landscape features on the microgeographic genetic structure of a resident songbird. Heredity, 117(2), 63-72.

Boreal Chickadee “Poecile hudsonica”. (2015, November 30). Retrieved from https://www.borealbirds.org/bird/boreal-chickadee

Boreal Chickadee Similar Species Comparison, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Boreal_Chickadee/species-compare/60411301

Cooper, S. J., & Swanson, D. L. (1994). Seasonal acclimatization of thermoregulation in the black-capped chickadee. The Condor, 96(3), 638-646.

Explore the habits of the breeding birds of Minnesota. (n.d.). Retrieved February 14, 2019, from https://mnbirdatlas.org/

Feeney, M. C., Roberts, W. A., & Sherry, D. F. (2009). Memory for what, where, and when in the black-capped chickadee (Poecile atricapillus). Animal cognition, 12(6), 767.

Gill, F. B., Mostrom, A. M., & Mack, A. L. (1993). Speciation in North American chickadees: I. Patterns of mtDNA genetic divergence. Evolution, 47(1), 195-212.

Hadley, A., & Desrochers, A. (2008). Winter habitat use by Boreal Chickadee flocks in a managed forest. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 120(1), 139-146.

Murray, D. L., Peers, M. J., Majchrzak, Y. N., Wehtje, M., Ferreira, C., Pickles, R. S., … & Thornton, D. H. (2017). Continental divide: Predicting climate-mediated fragmentation and biodiversity loss in the boreal forest. PloS one, 12(5), e0176706.

Otter, K. A. (Ed.). (2007). Ecology and behavior of chickadees and titmice: an integrated approach. Oxford University Press on Demand.

Nelson, R. (2013, October). Boreal Forest Biome. Retrieved from https://www.untamedscience.com/biology/biomes/taiga/

McLaren, M. A. (1976). Vocalizations of the boreal chickadee. The Auk, 93(3), 451-463.

Mossman, M. J., Epstein, E., & Hoffman, R. M. (1990). Birds of Wisconsin boreal forests. The Passenger Pigeon, 52(2), 153-168.

Smith, S. M. (1997). Black-capped chickadee. Stackpole Books.

Templeton, C. N., Greene, E., & Davis, K. (2005). Allometry of alarm calls: black-capped chickadees encode information about predator size. Science, 308(5730), 1934-1937.

Weflen, K. (2013, April). The Crossroads of Climate Change. Minnesota Conservation Volunteer. Retrieved from https://www.leg.state.mn.us/docs/2015/other/150681/PFEISref_2/MDNR 2009.pdf