Should Travelers Take State Department Advice? The Politics of Travel Warnings

Should Travelers Take State Department Advice?

The Politics of Travel Warnings

H. Bradford

1.30.19

First of all, I will admit that I have been writing about travel more often lately. It is an easy topic to write about so I am being a bit lazy as a writer (by contrast it took me over two weeks to write my November post about the history of World War I.) With that said, a travel topic that I have been thinking about lately is the politics of State Department travel advice. Before heading to El Salvador, I checked the State Department’s website for travel warnings. El Salvador is listed as “orange” on the State Department’s Travel Advisory Map. Orange means that a traveler should “reconsider travel.” This warning level is on account of violent crime and gang activity. The warning is far from reassuring for a traveler, but, what exactly does the color coded system mean? Further, the State Department is far from a neutral entity doling out useful travel advice. It is one of the main instruments of U.S. imperialism. With that said, I will explore this topic so that travelers can approach the State Department with skepticism.

Decoding the State Department’s Color Code:

The State Department divides the world into color coded warning levels. There are seven warning levels: Red (Do Not Travel), Orange Striped (Reconsider travel-Contains areas with higher security risk), Orange (Reconsider travel), yellow striped (Exercise caution-areas with higher security risk), yellow (Exercise caution), colorless stripe (Exercise Normal Precautions – Contains Areas with Higher Security Risk), and colorless (Exercise Normal Precautions). Thus, the State Department has developed a system of risk measurement based upon a nominal scale of colors and associated risks- with red being the highest risk and white being the least highest risk. Because they are nominal, they don’t have any quantitative value. For instance, very cold could appear on a nominal scale of weather. But, what does very cold mean? To someone from a tropical region, this could be 50 degree Fahrenheit. To another individual, this could be -40 degrees Fahrenheit. “Exercise Caution-Higher Security Risk” has about as much meaning as “very cold.” Within this system, Orange is different from Striped Orange or Red, but precise difference is unknown. Of course, risk is not easily measured and like “very cold” it depends upon who you are and your position in the world. The map would look different for a rich, white, heterosexual male American than a poor, Black, lesbian, Muslim American. A person’s risk in the world is impacted by access to resources that allow for safety.

The scale, while not particularly nuanced or scientific in its approach, creates a mental schema of how safe or unsafe the world is. This schema is not entirely baseless. After all, there is indeed crime and violence in El Salvador. However, the color codes speak more about the relationship to the U.S. government and the rest of the world than travel risks. For instance, Russia is categorized as yellow striped, on account of the risk of terrorism, harassment, and arbitrary enforcement of the laws. Police harassment and arbitrary enforcement of the law is not a uniquely Russian phenomenon and while there may be some cultural and political norms regarding policing, police interactions are shaped by race, class, gender, nationality, religion, and basically, one’s relationship to state power. Are Russian police fundamentally different from Bulgarian, Serbian, Romanian, Belarusian, Macedonian, or Georgian police? None of these other countries bear warnings or warning levels as high as Russia’s (Albania and Georgia are colorless striped or two tiers safer and the other countries are not colored.) Is Albanian really two tiers safer than Russia? Russia’s safety level is also on account of instances of terrorism, but there are other countries with higher instances of terrorism with lower safety risks (such as Greece). Granted, in 2017 there were 61 deaths in Russia on account of terrorism (according to Wikipedia). Thailand is ranked two tiers lower in risk, but 72 people were killed in incidents of terrorism in 2017. It seems to me that some of the ranking has more to do with countries that the United States does not get along with than actual risk.

Consider code red, or the highest level of risk. There are few countries that are deemed entirely unfit for travel. One is Yemen. This makes sense. The country is being blockaded, starved, and bombed by Saudi Arabia. North Korea, on the other hand, is actually a very safe place to travel in terms of low crime, social stability, and lack of terrorism (but extremely unsafe for those entering illegally or with intent to challenge government authority). Travel to North Korea resulted in the horrific and mysterious death of an American tourist, which is something which should not be minimized. But, this death is deeply political and certainly given more media attention than horrific, mysterious, but less political deaths of tourists in countries friendlier to the United States. For instance, in December, Carla Stefaniak was murdered in Costa Rica. Her partially naked body was found near her AirBnB with a stab wound to the neck. This death is horrific (though less mysterious since the murderer was found.) Yet, Costa Rica is not pegged as an unsafe place to travel (striped and not colored). Sexual violence against women does not spark the same fear and outrage as the state sponsored murder of a white male college student. Sexual violence is commonplace and women are often blamed for their victimization. The violence of a tyrannical state must be framed as exotic and uniquely cruel in order to justify U.S. imperialism, even if our own prison system routinely denies medical care to prisoners, as Otto Warmbier was denied adequate care during his North Korean imprisonment. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2661478/ ). This isn’t meant to defend North Korea, but simply to point out that tourists die in less politicized contexts without much alarm. Saudi Arabia dismembered a journalist in a Turkish consulate and that country ranks as dangerous as Russia to travel to. This garnered a great deal of media attention, but did not translate to warnings about Saudi Arabia. So again, travel advisories are a reflection of the international relations of the United States.

Returning to El Salvador, the country is ranked as orange, which offers that one should reconsider travel. Other “orange” countries include Chad, Nigeria, and Mauritania. It seems there quite a qualitative difference between El Salvador and say…Chad. Chad doesn’t have much for tourist infrastructure/industry, so a tourist is probably going to have a harder time insulating themselves from threats through the buffer of tourism. For instance, Chad was visited by about 115,000 tourists in 2015, whereas El Salvador was visited by over 1.4 million tourists that same year. Chad is one of the poorest countries in the world, is engaged in a fight against Boko Haram, is viewed by the international community as having a corrupt and authoritarian government, and also experiences violent rebellion in the north of the country. I would think that there is a difference in travel to El Salvador than travel to Chad, even if El Salvador has high levels of crime. Interestingly, the British government ranks Chad as a high travel threat and advises against all travel to the north of the country and border regions with only essential travel to the rest of the country. In contrast, the British government deems El Salvador incident free for most travelers who exercise caution. I am uncertain why the State Department would lump Chad and El Salvador together in the same category of danger unless this designation helps to support U.S. immigration policy, which seeks to portray Central American migrants as dangerous criminals and because Chad is such a non-entity to U.S. interests and travel that it doesn’t warrant a higher warning level.

British travel advisory map for Chad

We Make the World Unsafe:

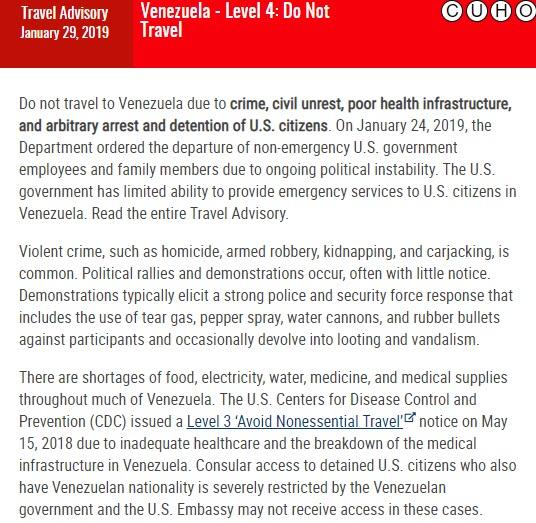

Another flaw of the U.S. State Department’s color code system is that it doesn’t describe why countries are coded as they are. For instance, in North and South America there are only two countries which are designated “striped orange” or the second highest level of threat. These two countries are Venezuela and Honduras. The State Department warns that in Venezuela there is the arbitrary arrest and detainment of American citizens. The warning says citizens plural, which implies it may be a common occurrence. In truth, an American citizen and former Mormon missionary named Josh Holt was arrested and spent two years in prison because it was believed by the Venezuelan government that he was stockpiling weapons and working for the CIA. Weapons and incriminating documents were found at his residence in Venezuela, but his mother claimed these were planted. It is difficult to know if this is a case of a framed innocent man or someone with terrorist intent. However, what is known is that the travel dangers in Venezuela do not exist in a vacuum and some of the conditions are created and exacerbated by U.S. foreign policy. For instance, the State Department warns travelers about the poor health infrastructure of Venezuela. This fails to mention that U.S. economic sanctions against Venezuela designed to force regime change by economically punishing the population into revolt and the economy into collapse. These sanctions have prohibited debt restructuring, borrowing from financial institutions, and the convertibility of Venezuelan currency. These tactics have made it harder to control hyperinflation and balance trade, which have contributed to murderous shortages of food and medicine. Yes, Venezuela may not be the safest place to travel to, but it would be much safer if the United States had not actively sought to overthrow the government and punish the population.

The other high risk level country is Honduras. The United States supported the 2009 coup in the country. By recognizing the Lobo (temporarily Micheletti) government and refusing to acknowledge the coup, aid to Honduras could continue as normal, including military aid that has been used to murder dissenters. Another consequence of our policy is that the tens of thousands of Hondurans who have fled the country are not recognized as political asylum seekers (to do so would be an admission that the U.S. supported government is indeed violently repressive). The State Department offers that Honduras is unsafe due to crime. Crime is an enormous topic that I have neither the time nor knowledge to address properly, but the crime in Central America is also a function of U.S. foreign policy. Murders increased in Honduras after the 2009 coup. The state has been behind some of these murders and state violence has empowered criminals, because violent crimes go unpunished or investigated. In any event, the orange striped color code bestowed upon Venezuela and Honduras is interesting since both countries have experienced U.S. supported coups and both have been destabilized by U.S. foreign policy. Thus, where a country falls in the color code system is often a result of U.S. meddling in that country. It is little wonder that most of the “red” or do not travel to countries are countries the United States is or has recently been at war with or invaded, such as Libya, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria.

Alternatives:

If one accepts the premise that going to the State Department for travel advice is about as reliable as going to your fascist grandpa for dating advice, then what is the alternative? (Note: my grandpas were cool and not fascists). The main entity that issues travel warnings are various government institutions. Every government has its own foreign policy interests and relationships and therefore biases in issuing warnings. But, even if there was a progressive institution for the issuance of travel warnings, travel safety is not something which is easily measured. For example, suppose there was a GDP type formula for travel danger. Perhaps it would look like Natural Disasters + Crime + Terrorism + Disease+ Animal Attacks +Industrial Disasters = Risk. Of course, there are other variables which could be included. However, some variables may be weighted more heavily than others due to the severity of their impact and commonality. An island that is literally nothing but an erupting volcano may not rank as high if it does not have crime, animal attacks, or terrorism. The variable of industrial disaster might be weighted more heavily depending upon the type of disaster. For instance, a reactor leaking radioactive material is of greater concern than a factory full of vats leaking molasses. There are probably some smart statistical and scientific people who could develop such a formula, but it seems that the variables are so expansive and subjective that this would not be easy. An easy measure would be the number of tourist deaths or injuries per the total tourist population. This would be useful information, but tourists may travel to “safe” destinations such as Iceland, but engage in dangerous behaviors (such as jumping into geysers or chartering private flights over erupting volcanoes). Finally, as I mentioned before, safety differs depending upon one’s access to resources. I have traveled to countries that rank pretty high on the State Department’s risk list, however, as a tourist, I am sheltered from some dangers. For instance, when I hiked up a volcano in El Salvador, the tourists were escorted by a police officer. The police officer is a state provided measure to ensure that tourists continue to visit the country and the volcano because they were not robbed or assaulted along the way. Governments often want tourism because it generates economic activity, so measures are taken to make sure that tourists are safe (sometimes at the expense of local populations if this includes dislocating homeless populations, bans on begging, busking, or loitering, increased policing, development that dislocates people or drives up housing prices, etc.) Aside from the protections enjoyed by tourists as a group, the relative safety of each individual tourist varies depending upon their class, gender, sexuality, religion, nationality, ability, age, etc. Perhaps an alternative to the State Department map would be a map of how unsafe you are depending upon different variables. For instance, a traveler who is LGBTQ might find that many countries are unsafe due to restrictive laws and punishing social norms.

On the other side of the equation, travel warnings or safety advisories are pretty one sided. It assumes that the victim is the tourist and that the danger in embedded in the destination. It would be interesting to see a reverse map depicting areas that tourists make unsafe. This sort of map would advise locals to avoid certain bars or neighborhoods that are frequented by tourists, lest they be physically assaulted by drunk tourists or sexually assaulted by entitled foreigners. Tourists are not hapless victims of a dangerous world. Tourists can create danger by vandalizing historic sites, defying local laws or customs, damaging environments, creating pollution, abusing service industry staff, sexually exploiting minors, reckless behavior, etc. In this case, Mali and Chad are comparatively safe….from tourists!

There probably is no answer of how safety can be measured. It is a political question. The question itself comes from a place of privilege. There is no shame in wanting to be safe, but the ability to go somewhere else and even ponder safety comes from a place of relative privilege to most of the world. At the same time, some places certainly are less safe on account of such things as war, disease, famine, or natural disasters. Using government warning systems to gain some sense of safety isn’t useless since it can create a starting point for further investigation. Ultimately, I don’t have an answer of how to gauge safety. Usually, I ask myself if people like me travel to the destination without incident? And, if there are incidents, what are they are how often do they happen? What kinds of measures can be taken to avoid unsafe situations? In the case of El Salvador, travel warnings did cause me some concern. Even online forums were divided between it’s awesome and safe to some sentiments of absolutely don’t go! So, when I was there alone for a few days, I didn’t venture out after dark and booked day trips in advance of my travel so that I could sight see in what I felt was a safe way. I also stayed at a nicer hotel than would be typical if my travels (I usually am fine with hostels). I felt extremely safe. In this case, I was probably overly cautious. If something terrible happens to me at some future date, I suppose I will be blamed for ignoring State Department advice. At the end of the day, like anything else in the world, the best approach is probably seeking out a variety of sources to determine the safety of a destination. Yes, this is pretty generic advice, but the main point that I wanted to convey is that the State Department is not the end all and be all of advice- in fact, its advice is shaded by U.S. relationships to the world and it is a significant reason why some countries are unsafe to begin with.

|

|