Capitalism and Self Care

Capitalism and Self Care

H. Bradford

3/27/19

Whenever I hear the word self-care, I feel a little skeptical. It seems like one of those feel good notions that activists and “helping” professionals ritualistically throw around to pay homage to burn out, compassion fatigue, or just the very human need for food, sleep, and health. The Marxist in me always feels a bit cynical about the whole thing. To me, self care seems self-evident. A world in which me must pause, consider our needs, and carve out some extra space and time to meet these needs seems extraordinarily exploitative. The concept itself seems atomizing, as the inability of capitalist society to meet human needs is placed upon the individual, who is tasked with adequately caring for themselves. At worst, it seems like a hedonistic excuse to retreat from society or struggle. Self-care seems like the chore of maintaining oneself just enough to continue to be miserable. Some of this pessimism regarding self-care is founded, but some of it is not. Indeed, self-care has radical roots which should be reclaimed to push back against the crisis of care created by capitalism.

Capitalism and the Crisis of Care

To begin, it is useful to examine care more generally and how “care” connects to capitalism. Care is often an invisible, expected, and taken for granted role for women in society. Women have long been associated with care, as in the care for children or care for families, but capitalism created the conditions wherein economic production and social reproduction separated into two distinct categories. In other words, capitalism created a dichotomy between waged work and “care” (Arruza, Bhattacharya, and Fraser, 2019). Economic production became something that happened inside of offices or factories, where it was remunerated with a wage (Leonard and Fraser, 2016). “Care” became the sentimentalized labor that women often do as a matter of love than for pay, and as such, it is not as valued or recognized in society (Arruza, Bhattacharya, and Fraser, 2019).

According to a 2015 report, 1.9 billion children under the age of 15 and 200 million older adults are in need of care. This number is expected reach 2.3 billion by the year 2030. Globally, among 64 countries studied, 16.4 billion hours per day are spent performing unpaid care work. 76.2% of this is done by women (Women do 4 times more unpaid care work than men in Asia and the Pacific, 2017). Around the world, women complete more unpaid labor in the home than men, wit the largest differences found in Asian countries such as Japan, China, India, and South Korea. Women also spend less time each day engaged in leisure activities. For instance, in the United States, women spend about 262 minutes eat day on leisure activities, whereas men spend about 305 minutes. In Greece, women enjoy 318 minutes of leisure, whereas men have 393 minutes each day. In Portugal, women have 200 minutes of leisure each day and men, 289 minutes (Taei, 2019). Among OECD countries, women complete 4.5 hours of unpaid labor each day or 271 minutes. In comparison, men average around 2.5 hours each day, or 137 minutes (Berman, 2017). The gender gap in unpaid labor starts young, as according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, teenage girls perform 38 minutes of chores each day, whereas teenage boys do 24 minutes of chores each day (Gollayan, 2019).

The lack of leisure time and large amounts of unpaid household care work, certainly create the conditions wherein women need self-care. Beyond unpaid labor preparing food, washing clothes, cleaning homes, caring for children, or tending to the sick, women are often relegated to exhausting, low paid, undervalued “caring” professions. 97.5% of kindergarten and preschool teachers are women, 94.4% of childcare workers, 94% of nurse practitioners, 89.9% of maids and housekeepers, 89% of teaching assistants, and 84.5% of personal care aids are women. Women make up the majority of the service industry, as they make up 80% of restaurant hosts, 72% of cashiers, 71% of non-restaurant food servers, 70% of waiters, and 66% of hotel front desk workers (Rocheleau, 2018). Thus, when women are not at home caring for children, workers, and retirees, they often find themselves thrust into paid care work, wherein they care for children, serve food, provide medical care, or care for the elderly. Cashiers, waitresses, personal care attendants, and hostesses each have an average income of under $22,000 a year, at least according to 2013 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Among teachers, those who serve younger ages make less. For instance, Kindergarten teachers average $52,800 a year, whereas secondary education teachers average $58,300 a year (Wile, 2015). Thus, those who engage in care work often face a wage penalty.

Image taken from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-03-03/a-female-cashier-works-in-a-supermarket/6276318

One way that the amount of care work that women engage in can be explained is through Social Reproduction Theory. According to Social Reproduction theory, capitalism charges women with the upkeep of capitalism. Social Reproduction posits that in order to perpetuate itself, capitalism needs both a future generation of workers and the upkeep of current workers, retired workers, and non-workers. Thus, historically women have been tasked with having children, raising children, caring for the elderly or people who cannot work, cooking, cleaning, other household chores, and all of the other, mostly unpaid labor that goes into ensuring that capitalism can continue. Much of this labor occurs within the family, but some social reproduction may be provided for by the state or private sector (Arruza, 2016). When the state engages in social reproduction, it can be said that the care work has been socialized. On the other hand, when the private sector engages in care work, it means it is commodified (Leonard and Fraser, 2016). For instance, when countries provide state funded day care centers or nursing homes, the state is engaged in the social reproduction of capitalism. However, as it will be argued later, many of the paid employees in such institutions are women. As a whole, women are often engaged in what is generally called “care work” which is paid and unpaid labor that involves the care of people, but can also include care for animals, communities, or environments. While care work is not a specifically Marxist term or a phenomenon that is unique to capitalism, care work is an essential component to capitalism’s continuation. Capitalism is contradictory as it does not provide for its own upkeep. It requires workers, yet the profit motive drives capitalism to lower wages and lessened working conditions The drive for profits also results in austerity, or cuts to social programs and the privatization of public institutions which provide care. This results in a crisis of care, in which women find that they have trouble balancing paid labor with reproductive labor (Arruza, Bhattacharya, and Fraser, 2019).

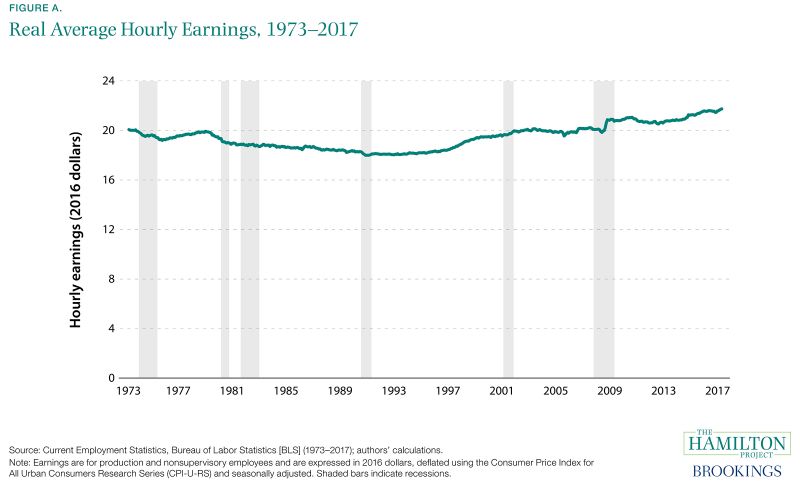

The Crisis of Care is a profound insight to the nature of capitalism and may offer why self-care is so popular and necessary. During the 20th century, many advanced capitalist societies expanded the state’s role in social reproduction. The global south did not experience this, as they were predated upon by imperialist powers of the north. A strong labor movement pushed for social reforms that shortened the work day, banned child labor, provided some social welfare programs, and ensured a family wage. However, racism within more advanced capitalist countries such as the United States meant that not all workers enjoyed these benefits equally and access to the “family wage” was predicated upon heteronormative monogamous relationships (Leonard and Fraser, 2016). Yet, in the last forty years in order to eke out profits in an increasingly competitive global economy, the gains of workers have been attacked in many ways. Following the post World War II boom, the United States began to lose its place in the world economically in the 1960s and 1970s as Japan and Europe rebuilt their economies. The United States also began to de-industrialize, as industrial union jobs went to more profitable, low wage, non-union places elsewhere in the world. The loss of these higher paying jobs put pressure upon women to enter the workforce as a single family wage was no longer adequate, though the feminist movement also pushed to break down barriers to entry into the paid economy as a matter of equality, freedom, and self-determination. Between 1970 and 2003, 60% of new jobs created went to women, yet at the same time wages have been stagnant. For the first time, white women began to engage in paid labor as much as Black women (who historically have not enjoyed the privilege of working only in one arena of the economy). Of course, much of this growth was in the service industry, though there was also growth in finance, real estate, and insurance industries (Eisenstein, 2005). These areas are interesting, because they are associated with what Marxist call fictitious capital, or a more unstable economic area where capitalists go when they’ve run out of space to invest elsewhere, so this sort of job growth is also indicative of the crisis of capitalism. While the United States was de-industrializing, there has also been a global push towards austerity and privatization (Eisenstein, 2005). It is little wonder then that in the face of attacks at work in the form of depressed wages, longer hours, less stability and also the loss of social benefits, that the crisis in care has driven women towards self-care to restore stability, wellness, and balance in their lives. Self-care offers a reprieve from the ravages of capitalism.

Just an image of Real Wages over time

The Commodification of Self Care

The economic conditions of capitalism limits the ability of workers to take care of themselves. Self-care may resonate with some women because they are stretched thin between paid and unpaid labor. It is little wonder then that in recent years, there has been increased interest in self-care. In 2017, there was an uptick in the self-care activities with a 17% increase in therapy, 34% increase in yoga, 16% increase in meditation, and 19% increase in daily walks (Daniels, 2018). There are over five million posts about self care on Instagram (Lieberman, 2018). Self-care became more mainstream after the 2016 election and was googled twice as much as in year following it (Aisha, 2017). The popularity of self-care related topics on social media contributes to differences in who engages in self-care. For instance, millenials spend twice as much as boomers on self-care. This younger demographic is more internet savvy, which allows them to search for self care ideas and get exposure to self care through social media (Silva, 2017). Problematically, self-care within capitalism is commodified and individualized. It also reflects of disparities in ability, rage, class, sexuality, gender, and other areas of oppression. For example, the beauty industry is quick to appropriate “self care” as a means to sell products. Ofra Cosmetics used the slogan “Turn Your Skin Care Routine Into A Self-Care Ritual,” to turn using skin care products into an act of self-care (Boyne, 2018). By 2024, the skincare industry is estimated to grow to $180 billion and even congress member Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez shared her skincare routine on Instagram, divulging that she keeps makeup wipes by her bed to allow her skin to breathe. Healthy skin is seen as virtuous, rather than a signifier of wealth (Hill, 2019).

An advertisement for Mad Peaches Med Spa- http://madpeachesmedspa.com/skin-care-is-self-care/

One of the more obvious examples of the commodification of self-care is, Gwyneth Paltrow, who made $250 million by selling wellness products under her brand Goop. The company sells such things as emotional detox bath soaps and vaginal steams (Daniels, 2018). These products fleece women of their money in the interest of classist and gendered notion of what it means to care for oneself. Self-care could be a $10 tube of Goop toothpaste, an $85 medicine bag containing several crystals, or a $3500 gold sex toy (K., 2018). In 2017, the self-care industry was estimated to be worth $4.2 trillion globally. Over the past two years, the industry has a growth rate of 6.4%, which is twice the growth rate of the entire global economy. The largest component is anti-aging, skin care, and beauty, which makes up $1.08 trillion. Another area of growth in the self-care industry is food, of which, foods categorized as keto, plant based, probiotic, low sugar, paleo, vegetarian, flexitarian, and gut healthy are the top food trends in 2019. Athletic wear, cannabis, and low cost gyms are also areas of growth within the self-care industry (Low, 2018).

“Self Care for the Cubicle Bound”- From Goop- https://goop.com/beauty/makeup/self-care-cubicle-bound/

Self-care often gets mashed together with self-improvement and might be viewed as a modern iteration of this long standing theme in Western culture. For instance, Socrates advised that young men should not enter political leadership until they have worked on themselves. Foucault observed that cultivating the soul and self was part of the thinking of Seneca, Epictetus, and many early Christian thinkers. In U.S. history, the concept of self-care was used towards racist ends, as Samuel Cartwright justified slavery because slaves were unable to care for themselves on account of their inferior race. Scholar, Matthew Frye Jacobson used a similar argument against immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, as he claimed they were unable to care for themselves. The argument was also used to justify denying women the right to vote (Kisner, 2017). Within the self-care industry, the self-improvement industry is worth $11 billion. Mindfulness meditation, which seems like something that could be done for free, is a $1 billion industry (Lieberman, 2018). This aspect of self-care is dangerous for several reasons. Firstly, it does not challenge the notion that a person’s worth is predicated upon their efforts towards self-improvement. As illustrated earlier, hierarchies of better or more capable selves and lesser capable selves, was twisted into arguments against immigration, women’s suffrage, and for slavery. Self-care is racialized inasmuch as wellness is often depicted as a pastime for white women. The arena of self care is often a white space designed for white women and wherein other white women profit (Daniels, 2018). Self-care naturalizes wellness as white while rendering the outcomes of self-care as virtuous (healthy skin, fit bodies, physical ability). Secondly, because self-improvement costs money, it creates a divide between who can improve and who cannot. Wellness is reserved for the wealthy who can afford the time and money for such things as expensive fitness classes, skin products, or foods. Because self-care is an individual endeavour, it does not address or contextualize social problems such as poverty (Daniels, 2018). Finally, it is simply stressful and laborious to improve oneself, especially when people are already overburdened with paid and unpaid labor. In a UK study of 200 women who used fitness trackers, 79% felt guilty if they did not meet their daily goals, 59% felt controlled by the device, and 30% felt like it was the enemy (Lieberman, 2018).

This newest, commodified version of self-care is a new capitalistic incarnation of the concept, but it has meant different things throughout history. The Civil Rights movement and feminist movement engaged in self-care as a political act as a reaction to the failures of white, patriarchal society to care for their needs. Part of the early movement for self-care entailed setting up women’s health clinics to address the health needs of women as an alternative to medical institutions which many women experienced as sexist and hostile to women’s health. Self-care was also a component of The Black Panther Party’s orgazing. The Black Panthers sought to address community needs that had been unmet by the state. As such, they set up clinics to address the needs of black people, such as testing for sickle cell anemia or lead poisoning (Aisha, 2017). The Black Panthers established thirteen free clinics around the the country and connected poor health as an outcome of poverty (Bassett, 2016). Today’s concept of self-care, which focuses on the individual and is far less political and community based. Another understanding of self care is the medical term employed in high stress jobs such as social workers, therapists, and EMTs, who recognized the need for self-care to avoid burn-out or compassion fatigue. This use of the term is certainly not as radical as the Black Panther or feminist movement concept of community building, but at the very least recognizes that work can be a source of personal strain. During the 1980s and 1990s, self-care became disassociated from its political roots and more connected to commercialized fitness and wellness trends that appealed to middle class white people. Fitness clubs and yoga classes are the types of ways that self care has manifested since then. In recent years, feminists and activists in the black community have shown renewed interest in self-care as well (Aisha, 2017). After the mass shooting in Orlando, LGBTQ people around the world used the hashtag #queerselflove to post selfies and Jace Harr, a trans man, created a popular online questionnaire entitled, “You Feel Like Shit: An Interactive Self-Care guide” which asks users if they have drank water, feel disassociated, feel triggered, and other self-care questions. Devin-Norelle, a trans black man, posted about self care after the murders of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, saying “Healing is self-care is self-love, self-indulgence, and self-preservation, because sometimes we need to be reminded that #BlackIsBeautiful (Kisner, 2018).” Devin-Norelle’s post echoes a quote from Audre Lorde, who wrote, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare (Boyle, ND).” Similarly, Evette Dione wrote in Bitch Magazine that many people are poor, working themselves to early graves, and that self-care means pushing against society by asserting one’s own needs and existence (Kisner, 2018).

An image depicting the Black Panther’s Free Food Program- one of several social programs including clinics, food distribution, children’s breakfast program, and free ambulance. From: https://atlantablackstar.com/2015/03/26/8-black-panther-party-programs-that-were-more-empowering-than-federal-government-programs/

Conclusion:

Care often falls upon the shoulders of women. Women are often tasked with caring for children, elderly, those who are ill, their communities, and the environment. This is done in both the paid and unpaid economy. The strain of this physical and emotional labor leaves little time for self-care, but a strong need for it. Capitalism commodifies self-care, turning it into something that requires time, effort, and money and bestowing virtues upon those who can accomplish balance, health, beauty and fitness. While self-care could be liberating, in this economic context, it is another trap. It is time to return to the roots of self-care. Today’s society needs the militant, collective self-care. Pressure should be put on the state and our workplaces for parental leave, paid sick time, healthy environments, socialized health care, free and expanded public transportation, living wages, affordable housing, reproductive justice, and all of the other things that are needed to live full and healthy lives. Self-care must connect the self to the social struggle and build up people together as communities. We must care for another, while empowering each other to fight for the structural changes necessary to end sexism, racism, heterosexism, poverty, ableism, and all other forms of oppression once and for all. Chocolates, bubble baths, and yoga are alright, but self-care should be enjoyed with a revolutionary consciousness that seeks to end the child slavery that produces the chocolate, the cultural appropriation that decontextualizes yoga among white people, and fights for access to clean water for all! I suppose this sort of self-care is pretty exhausting, since it isn’t self-care as much as it is struggle. But, perhaps we can do self-care together, caring for each other along the way, so that we have strength and energy in each other. Finally, I think there is an important self-care tactic within the International Women’s Strike movement. This is the tactic of striking, which is withdrawing labor. Self-care can mean withdrawing unpaid and paid labor to demand better conditions and a better world. The ultimate way we can take care of ourselves is to work towards a world wherein we don’t have to work with such effort, little pay, lack of control, and uncertainty.

Sources:

Arruzza, C. (2016). Functionalist, determinist, reductionist: Social reproduction feminism and its critics. Science & Society, 80(1), 9-30.

Arruzza, C., Bhattacharya, T., and Fraser F. (2019). FEMINISM FOR THE 99%. New York: VERSO.

Bassett M. T. (2016). Beyond Berets: The Black Panthers as Health Activists. American journal of public health, 106(10), 1741-3.

Berman, J. (2018, April 15). Women’s unpaid work is the backbone of the American economy. Retrieved from https://www.marketwatch.com/story/this-is-how-much-more-unpaid-work-women-do-than-men-2017-03-07

Boyle, S. (n.d.). Remembering the Origins of the Self-Care Movement. Retrieved from https://bust.com/feminism/194895-history-of-self-care-movement.html

Boyne, I. (2018, November 15). Self-care must separate itself from beauty industry. Retrieved from http://miscellanynews.org/2018/11/14/opinions/self-care-must-separate-itself-from-beauty-industry

Daniels, J. (2018, December 05). Opinion | This Holiday Season, Resist The Unbearable Whiteness Of Wellness. Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/opinion-wellness-holidays-trump-gwyneth-paltrow-goop_us_5c07e65de4b0fc23611249c6

Eisenstein, H. (2005). A dangerous liaison? Feminism and corporate globalization. Science & Society, 69(3), 487-518.

Hill, J. (2019, March 19). Self-Care And Skin Care. Retrieved from https://the1a.org/shows/2019-03-19/self-care-and-skin-care

K., S. (2018, September 11). How Self-Care Became a $250 Million Business. Retrieved from https://www.couturesquemag.com/single-post/goop-self-care-politics-and-profit

Kisner, J. (2017, June 19). The Politics of Conspicuous Displays of Self-Care. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-politics-of-selfcare

Leonard, S., & Fraser, N. (2016, Fall). Capitalism’s Crisis of Care. Retrieved from https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/nancy-fraser-interview-capitalism-crisis-of-care

Low, E. (2019, January 28). Self Care Wellness Trends: Beauty, Fitness, Cannabis Fuel $4 Trillion Market. Retrieved from https://www.investors.com/news/self-care-wellness-trends-beauty-fitness-cannabis-market/

Gollayan, C. (2019, March 05). Teenage girls do more homework and household chores than boys: Study. Retrieved from https://nypost.com/2019/03/05/teenage-girls-do-more-homework-and-household-chores-than-boys-study/

Harris, A. (2017, April 05). How “Self-Care” Went From Radical to Frou-Frou to Radical Once Again. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2017/04/the_history_of_self_care.html

Lieberman, C. (2018, August 10). How Self-Care Became So Much Work. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2018/08/how-self-care-became-so-much-work

Rocheleau, M. (2017, March 07). Chart: The percentage of women and men in each profession – The Boston Globe. Retrieved from https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2017/03/06/chart-the-percentage-women-and-men-each-profession/GBX22YsWl0XaeHghwXfE4H/story.html

Silva, C. (2017, June 04). The Millennial Obsession With Self-Care. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2017/06/04/531051473/the-millennial-obsession-with-self-care

Taei, P. (2019, March 08). Visualizing Women’s Unpaid Work Across the Globe (A Special Chart). Retrieved from https://towardsdatascience.com/visualizing-womens-unpaid-work-across-the-globe-a-special-chart-9f2595fafaaa

Wilding, M., & Wilding, M. (2018, August 15). When Self-Care Turns into Self-Sabotage – Great Escape – Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/s/greatescape/when-self-care-turns-into-self-sabotage-489cef9859e5

Wile, R. (2015, June 13). This epic chart shows the average wage for almost every job in America. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/the-average-wage-for-almost-every-job-in-america-2015-6

Women do 4 times more unpaid care work than men in Asia and the Pacific. (2018, June 27). Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/asia/media-centre/news/WCMS_633284/lang–en/index.htm