Growing Injustice: Several Problematic Plants

Growing Injustice: Several Problematic Plants

H. Bradford

6/4/18

Warm weather is finally here, so I have spent the last two weeks readying my garden for the season. Since I’ve been planting more, I have plants on the brain. Lately, I have been thinking about plants and issues of racism (and in one case, anti-semitism). Some plants have some very questionable names. Other plants have racially sensitive histories that social justice minded gardeners should consider. Plants like Wandering Jew, Kaffir lime, Nyjer seed, Indian Paintbrush, and even Collard Greens may be taken for granted by most growers, but contain issues of race and ethnicity. Thus, the following blog post offers an overview of some of these offenders, so that we can grow gardens as well as a more just world for everyone! (The list of problematic plants is not comprehensive. I also did not cite sources within the text, but a list of links that I drew from can be found at the end).

Wandering Jew:

If you visit a greenhouse, you may find a plant called a Wandering Jew. There are several plants that bear this name, including three species of spiderwort plants, four species of dayflower, and two other plants. The spiderwort species are the sort that seem most commonly used as indoor plants. A few years ago, a local greenhouse recommended a Purple Wandering Jew plant for our home, since they can grow in lower light conditions. The employee assured my housemate and I that there was nothing antisemitic about the bushy, viney plant.  The term Wandering Jew comes from 13th Century Christian folklore. The character is a Jewish man who was said to have taunted Jesus before he was crucified. As punishment for his taunt, he was cursed to walk the Earth until the return of Christ. In some stories, his clothes and shoes never wear out and after 100 years, he returns to being a younger man. He was a perpetual traveler, unable to rest, but able to converse in all of the languages of the world. This is not based on any actual Biblical story, though it may have been inspired by the story of Caine and European paganism. Much like Big Foot or ghosts today, Europeans of the time believed that they had actually seen this character. For hundreds of year, even into the present day, this character has appeared in literature and art.

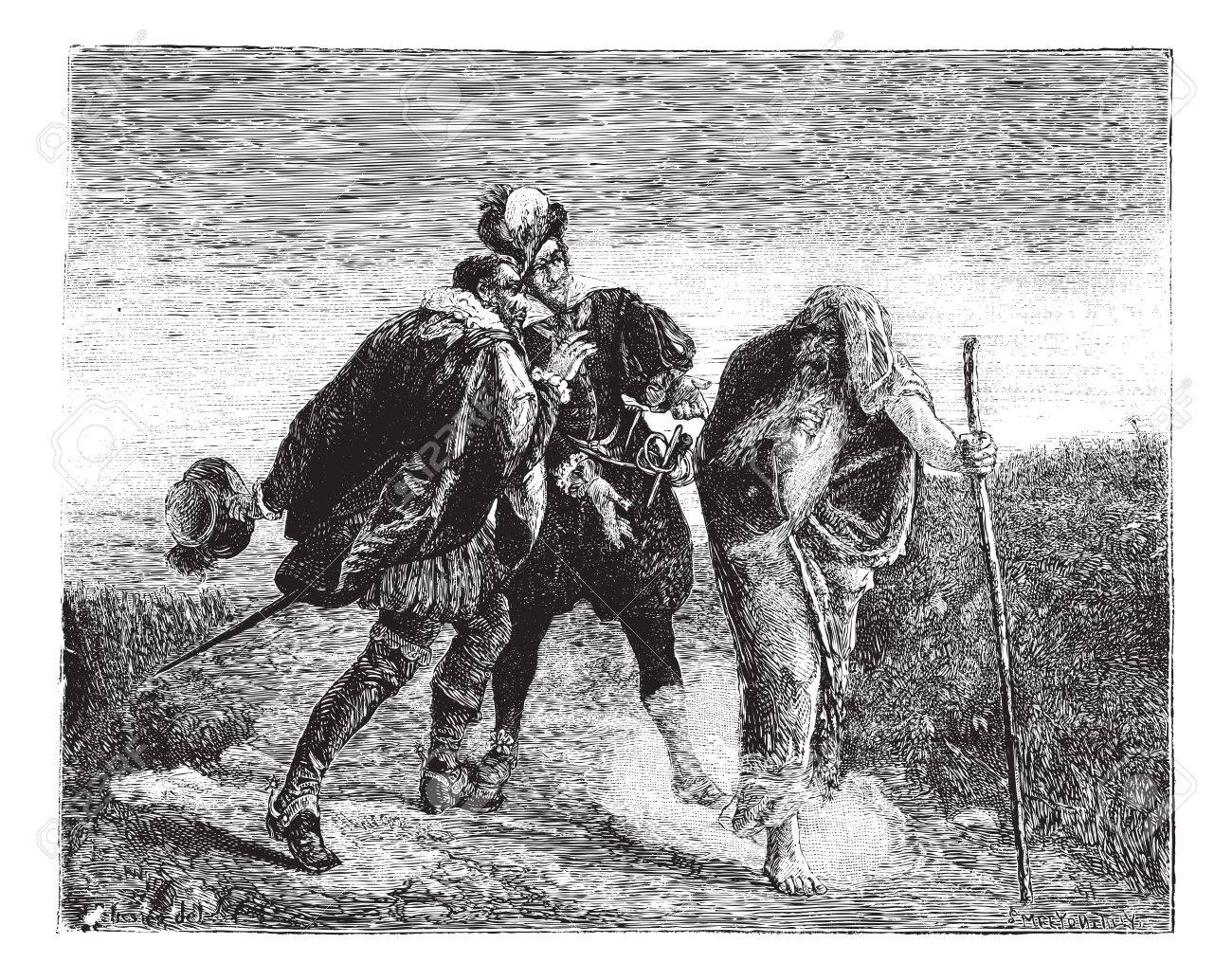

The term Wandering Jew comes from 13th Century Christian folklore. The character is a Jewish man who was said to have taunted Jesus before he was crucified. As punishment for his taunt, he was cursed to walk the Earth until the return of Christ. In some stories, his clothes and shoes never wear out and after 100 years, he returns to being a younger man. He was a perpetual traveler, unable to rest, but able to converse in all of the languages of the world. This is not based on any actual Biblical story, though it may have been inspired by the story of Caine and European paganism. Much like Big Foot or ghosts today, Europeans of the time believed that they had actually seen this character. For hundreds of year, even into the present day, this character has appeared in literature and art.

Gaston Malingue’s painting “The Wandering Jew”

While the character is very fictional, the antisemitic context the character was born from is not. In 1290, Edward the I expelled all Jewish people from England. During the middle ages, Jews were banned from owning land. They were also barred from trade guilds. Medieval cities also relegated Jewish populations to certain areas. In the 14th century, Jews were expelled from France, Germany, Portugal, and Spain. Expulsions and exclusion from various economic activities provided a material reality for the idea that Jewish people were outsiders or wanderers. Thus, “The Wandering Jew” represents not only a person, but a stereotype regarding the nature of all Jewish people. This stereotype has been used in modern times to incite hate, such as the Nazi film entitled “Der Erwige Jude,” which revived and modernized the medieval myth and envisioning modern Jewish people as criminal, lazy, and perverse cosmopolitans who controlled the world through banking, commerce, politics, and the media. The idea of the Wandering Jew has

With this history in mind, calling a rambling, hard to destroy plant a “Wandering Jew” does not seem like the most culturally sensitive nomenclature, to say the least. Interestingly, the Swedish Cultural Plant Database (SKUD) has changed the name of the “Wandering Jew” plant as well as another plant with an anti-semitic name (Jew Cherry which we know as Chinese Lantern Plants). I am uncertain what SKUD renamed the plant to, but perhaps Purple Spiderwort, Variegated Spiderwort, or Wandering Spiderwort might be some good ideas. There are other plants with “Jew” in their title and these should be changed as well. While not a plant, no one should call a wood ear mushroom a Jew’s Ear. I could find no similar examples of plant names that are unflattering/prejudiced towards Christians or other religious groups, but if there were and even if the group did not share the same history of oppression and genocide, there seems no reasonable argument to use derogatory common names. If I saw such plants at a local store or greenhouse, I would suggest a name change to the manager.

Collard Greens:

A few years ago, I planted collard greens. I was curious about this vegetable and wanted to grow it because I enjoy trying new things. However, my housemate suggested that the name was racist since it sounds like “Coloured Greens.” The leaf green is associated with African American cuisine, so it seemed plausible that the name may have had a more racist origin. Thankfully, it doesn’t! The word Collard comes from “colewort” in Middle English perhaps influenced by Old Norse “kal” for cabbage, and earlier still, kaulos, which is Greek for stalk. The “Col” and collard is found in other words like cauliflower, kale, coleslaw, German kohl for cabbage, etc.

While the leafy green is more prominent in the cuisine of the Southern United States, it is also used in Brazilian, Indian, and Portuguese cooking. It was cultivated in Greek and Roman gardens 2000 years ago as is closely related to kale. Prior to this, it is theorized that wild cabbages were in cultivation in Europe 3000 years ago and up to 6000 years ago in China. Leafy cabbages were also grown in Mesopotamia. While collard greens in particular (in contrast to other leafy cabbages) have long been consumed by Europeans, the history is not devoid of racism or contention. A controversy arose a few years ago when Whole Foods Co-op suggested that customers buy collard greens and prepare them with ingredients such as cranberries, garlic, and peanuts. Some African Americans felt that this was cultural appropriation of a vegetable used in their cuisine and food gentrification of a vegetable by white people who have recently discovered it and have now re-imagined it as something trendy. This critique is not unfounded. Afterall, Neiman Marcus sold out of their $66 frozen trays of collard greens in 2016. Historically, collard greens, like many members of the cabbage family were poor people food. (Though Romans actually esteemed cabbages as medicinal and a luxury.) Members of the cabbage family are cool season crops with mild frost resistance, making them part of winter staples or lean time food.  African Americans came to the United States as slaves and were only allowed to grow a small selection of vegetables for themselves. Collards were one of them. While the vegetable is not African in origin, the methods of preparation were. West Africans use hundreds of species of leafy greens and prepare them in ways that maintain their high nutrient content. Enslaved Africans found fewer wild greens here and came to rely on collards, which were brought here by the British. (Depending upon where the slaves were taken from, they may have been familiar with leafy cabbages as in the Middle Ages, cabbages of various sorts were traded into Africa through Morocco and Mali). They are unique among cabbages in that they can continue to produce leaves over their growing season. They can be harvested for months when other vegetables quit in the cold weather. Collards helped slaves to survive due to their productivity. For this reason, poor white people also grew collards. It is a cheap, productive, healthy plant. Although white Southerners grew the plant, it was a marginal crop to European settlers and African Americans deserve credit for popularizing the use of greens and their preparation.

African Americans came to the United States as slaves and were only allowed to grow a small selection of vegetables for themselves. Collards were one of them. While the vegetable is not African in origin, the methods of preparation were. West Africans use hundreds of species of leafy greens and prepare them in ways that maintain their high nutrient content. Enslaved Africans found fewer wild greens here and came to rely on collards, which were brought here by the British. (Depending upon where the slaves were taken from, they may have been familiar with leafy cabbages as in the Middle Ages, cabbages of various sorts were traded into Africa through Morocco and Mali). They are unique among cabbages in that they can continue to produce leaves over their growing season. They can be harvested for months when other vegetables quit in the cold weather. Collards helped slaves to survive due to their productivity. For this reason, poor white people also grew collards. It is a cheap, productive, healthy plant. Although white Southerners grew the plant, it was a marginal crop to European settlers and African Americans deserve credit for popularizing the use of greens and their preparation.

image from Foodnetwork.com

I love plants. I love gardening. I have no problems eating vegetables. But, collard greens do raise the question of how white people (at least those who aren’t poor and from the south) should approach collard greens. On one hand, when food is gentrified, the cost goes up for those who have traditionally eaten it. For instance, after kale was deemed a superfood, its cost rose 25%. If food prices rise, it can drive poor people to unhealthier, cheaper foods. Collard greens are also a problem when they are commercialized and fetishized. Judging by the tone and content of internet articles on this topic, I don’t know that most African Americans would take issue with a white individual growing a small amount of collard greens for personal, private use for love of gardening and attempting to try new vegetables. In the case of Whole Foods and Neiman Marcus, it represented capitalizing on and changing the culinary traditions of Black people. The foods were presented in inauthentic ways, devoid of history, and for profit by cashing in on a contextless notion of the exotic. Since the vegetable is tied to the traumatic history of survival and slavery and has cultural importance (such as a feature of New Year’s meals) it isn’t something to take lightly. Collard greens have double the iron and protein than kale and 18% more calcium, so there may be legitimate reasons that many people should grow them. Personally, I am curious about many vegetables. Does my curiosity “Colombusize” the culture, culinary traditions, or agriculture of others? In small ways, yes. My hope is that I can be mindful of my decisions and the history/power embedded in even the simplest things.

Nyjer Seed:

Anyone who wants to attract finches to their yard may be familiar with nyjger seed, which is also called thistle seed. The seed does not come from the thistle plant and the name “nyjer seed” seems suspiciously like another n word. When I was a kid, the seed was spelled “niger” which also makes the seed a little suspicious. We pronounced it in a way that is similar to Nigeria or Niger in Africa. Unfortunately, some people did not pronounce it this way and instead thought it was pronounced like a racial slur. The bird seed industry actually changed the name of the seed because it had confused people or had been mispronounced. Nyjer is the 1998 trademarked name of the Wild Bird Feeding Industry.  While the name might suggest that the seed came from Nigeria or Niger, nyjer seed actually comes from the Guizotia abyssinica plant which grows in the highlands of Ethiopia. I found a reference to the seed being called Nigerian thistle, which to me indicates that whomever named the seed must have had some confusion about the geography of Africa or, perhaps generically called it “niger” seed as a stand in for Africa itself. Nigeria, Niger, and the Niger River are all located in West Africa whereas Ethiopia is in East Africa. The genus Guizotia contains six species, of which five are native to Ethiopia. A distribution map of the species shows that it grows naturally in some areas of Uganda, Malawi, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sudan. It also grows in India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Nepal. The plants found in and around India are believed to have been brought there long ago by Ethiopian migrants, who also brought millet to the region. Therefore, Nyger seed really has nothing to do with the countries of its (former) namesake and represents a sort of “imagined Africa” rather than any geographical or botanical reality.

While the name might suggest that the seed came from Nigeria or Niger, nyjer seed actually comes from the Guizotia abyssinica plant which grows in the highlands of Ethiopia. I found a reference to the seed being called Nigerian thistle, which to me indicates that whomever named the seed must have had some confusion about the geography of Africa or, perhaps generically called it “niger” seed as a stand in for Africa itself. Nigeria, Niger, and the Niger River are all located in West Africa whereas Ethiopia is in East Africa. The genus Guizotia contains six species, of which five are native to Ethiopia. A distribution map of the species shows that it grows naturally in some areas of Uganda, Malawi, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sudan. It also grows in India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Nepal. The plants found in and around India are believed to have been brought there long ago by Ethiopian migrants, who also brought millet to the region. Therefore, Nyger seed really has nothing to do with the countries of its (former) namesake and represents a sort of “imagined Africa” rather than any geographical or botanical reality.

Field of Nyjer Seed plants in Ethiopia

While in the United States, most people feed the oily black seeds to birds, it is used in the cuisines of India and Ethiopia. It has been been grown in Ethiopia as an oil crop since antiquity and today, makes up 50% of Ethiopia’s oil seed production. Overall, the main producer of commercial nyjer seed is India, followed by Myanmar and Ethiopia. About 50,000 metric tons of the seed are imported each year into the United States. It is the only commercial bird seed which is largely imported. This seems to be a tremendous amount of seed- which ultimately goes to bellies of wild birds! The use of nyjer seed seemingly follows the rise of the U.S. as a post-war global power. Bird feeding became more common through the 1950s, which resulted in demand for commercial bird food. As people increasingly fed birds, it became apparent that certain seeds were likely to attract different (more socially desirable) species of birds. Nyjer seed was adopted as a bird food in the United States in the 1960s. The first tube feeders used for the seed became commercially available in 1972. In the late 1960s, the seed had to be treated with heat, because it was often accompanied by the seeds of invasive weeds. All nyger seed imports must be subjected to 250 degree heat sterilization treatment.

image from Northwest Nature Shop

Despite small scale experiments, Nyjer is not currently grown in North America, and in an experiment between N.A grown seen and Ethiopian seed, the birds preferred the Ethiopian grown seed. Reading between the lines, it is important to think about what the import of this seed actually means. Various countries have tried to grow this seed, including the Soviet Union under the guidance of Ivan Vavilov. However, the plants do not yield enough seeds to make it economically viable. The region of India which produces the most seed is Madhya Pradesh, which is the sixth poorest part of India (per capita GDP). The regions which grow the seed are also home to ethnic minorities, such as Nagar Haveli which is the home of the Warli tribe. While I could find no articles which specifically addressed the plight of nyjer seed farmers, it stands to reasoning that because the center of production for these seeds are underdeveloped countries (and even greater underdeveloped regions within those countries) that the work conditions of those farmers is probably characterized by low pay, long hours, and hard work. Since some of these countries actually used these seeds as an oil and a human food, the movement towards exporting the seeds to the West as bird food has likely reduced its use as a subsistence crop. Finally, the fact that it has not been viable in the agriculture of more developed countries means that it is probably a labor intensive crop (and our labor is too expensive due to labor laws, organization) hence, the fact that it is imported rather than domestically grown.

Personally, I love birds. I want to attract finches to the yard and provide them with a fatty, seed that they love. At the same time, it certainly represents a lot of privilege that I can buy imported seeds (sometimes eaten by humans) to give to the birds. The origin of the seed itself is obscured by its name. There seems to be a lot wrong with nyger seeds. I think that my task as a socialist is to learn more about the specific labor conditions related to the seeds (since there is not a lot of information out there). If there was more awareness regarding the seeds, perhaps there would be more interest in fair trade or better working conditions for those producers. It is also possible that I could try growing my own seeds for the birds rather than relying on expensive imported seed. Nyger seed as been experimentally grown on a small scale in Minnesota. I think it is a fascinating seed with a wealth of history. At the same time, more should be done to illuminate the history and economic conditions of the seed.

Image from The Zen Birdfeeder

Kaffir Lime:

About a year ago, I picked up some gardening books from the library. One of the books was about growing citrus indoors. It introduced me to the Kaffir Lime. I really didn’t think anything of this name at the time. It sounded vaguely Middle Eastern, but I didn’t associate it with any particular meaning. Little did I know that kaffir is actually a racist term. The k-word is a racial slur in South Africa. The k-word was used in Arabic to describe non-believers, but was used by European colonists in South Africa to describe the African population. The word is so offensive, that there have been legal actions taken against those who have used the slur in South Africa. The name of the lime itself may come from Sri Lanka, where the lime is grown and where there is an ethnic group which self identifies as kaffirs. It is also possible that the fruit literally referred to non-believers, as it may have been named by Muslims who saw it cultivated by non-Muslims in Southeast Asia. However, because the word is racially offensive in most other contexts and considered hate speech in South Africa, a different name is an order. In Southeast Asia, the fruit is called Makrut, which has been suggested as a viable name change.

Indian Paintbrush:

While this example is not as offensive as the k-lime, there are many plants that are named “Indian x” such as Indian Paintbrush, Indian posy (butterfly weed), Indian Blanket (Firewheel), Indian pipe, Indian grass, etc. There are many North American plants which have common names which invoke something related to Native Americans. However, the way that these common names are used are not accurate, flattering, or supportive of Native Americans. For instance, Indian Paintbrush sounds quaint. As a child, I imagined that perhaps the flowers were really used as paint brushes by Native Americans. Indian Paintbrush, also called Prairie Fire, was used as a leafy green, medicine, and shampoo by some Native Americans. But, it was not used as a paintbrush. While the flower may resemble a brush covered in bright red paint, it could easily be called Paintbrush plant. Using the word “Indian” invokes something wild, mythical, or even something silly (such as literally using the plant as a paintbrush). It reduces Native Americans into an idea about something primitive, whimsical, or even non-existent rather than actual, living people, with actual uses for plants. This is true of the other plants as well. Many of the “Indian” plants are wild plants that are not commonly domesticated (though some are used in ornamental or “Native” gardens. There is also a colonizing tone to these names, as these are not the names that Native Americans themselves gave the plants but imagined names from colonizers and their descendents. There are often alternate common names for these plants, so there is no excuse to call them names which invoke a mythical idea of Native Americans. Better yet, maybe some of the plants could be given names from actual Native American languages. This would demonstrate that Native Americans knew, used, and named these plants long before the arrival of settlers. For instance, Ojibwe called the Indian Paintbrush plant Grandmother’s Hair (though I don’t know what this translates to in Ojibwe). Since plants were used by many tribal groups for different purposes, it would be difficult to determine which language should take precedence over another. At the very least, I think it is important to be mindful of language and consider existing alternative names (which I haven’t always been, since I was raised calling certain plants Indian Pipe or Indian Paintbrush).

image from Wikipedia

Conclusion:

There will always be some people who feel that these issues are no big deal. Some of these people feel that there is nothing offensive about using traditional plant names or that they know a Jewish person who doesn’t mind “Wandering Jew” or a Native American friend who likes to call plants Indian Paintbrush or Indian Grass. The world is diverse and certainly there are diverse opinions on these matters. To those folks, this probably seems like much ado about nothing. On the other hand, others may feel that issues of racism or oppression in general are much bigger than the kind of bird seed we use or what we call a lime. It is better to focus on the big picture than get caught up in the nuances of language. As for myself, I feel that this is a fascinating topic to think about and that to me, it uncovers subtle and not so subtle ways that various kinds of oppression are built into something as simple as what we call a plant or what we grow in the garden. For me, thinking about these topics is intellectually satisfying (I am interested in learning more about the history of plants) as well as a way for me to be a better, more mindful activist. At the end of the day, helping to grow social movements is far more important than the plants that we grow and know. Growing as an activist means working with others in organizations towards social change, but also the internal change that comes with challenging assumptions and rethinking what is taken for granted. With that said, hopefully this post helps others to grow in how they think about plants, but also their place in society.

Sources on Wandering Jew:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2009/feb/21/wandering-jew-history

https://sputniknews.com/art_living/201709151057426161-sweden-anti-semitic-plans/

https://www.theholocaustexplained.org/anti-semitism/medieval-anti-judaism/who-and-where-were-medieval-jews/

https://www.history.com/topics/anti-semitism

Sources on Collard Greens:

http://www.vegetablefacts.net/vegetable-history/history-of-cabbage/

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/08/18/kale-compared-to-other-vegetables_n_3762721.html

https://www.wral.com/lifestyles/travel/video/13531214/?ref_id=13531197

http://www.ebony.com/life/hungry-for-history-collards

The Humble but Hardy Leaf That Defines Our National Character

http://www.latibahcgmuseum.org/why-collard-greens/

http://abc7chicago.com/food/neiman-marcus-sells-out-of-$66-collard-greens/1589488/

https://www.trulytafakari.com/ate-white-peoples-collard-greens-tasted-like-oppression/

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/people-and-culture/food/the-plate/2016/09/5-foods-from-africa/

https://everydayfeminism.com/2015/11/foodie-without-appropriation/

Nyger Seed Sources:

https://www.topcropmanager.com/corn/niger-seed-production-is-for-the-birds-13172

https://www.petcha.com/nyjer-black-oil-sunflower-bird-seeds-a-history/

http://www.birdchick.com/blog/2009/12/growing-nyjer-thistle-in-north-america

http://www.manoramagroup.co.in/commodities-niger-seed.html

https://www.mprnews.org/story/2011/11/30/winegar

https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/139533/SB571.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Click to access Niger__Guizotia_abyssinica__L.f.__Cass._136.pdf

K-Lime Sources:

![2[1]](https://brokenwallsandnarratives.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/21.png?w=492&h=412)